Top Research in Lupus Nephritis Presented at ACR Convergence 2025

CHICAGO—Renal involvement occurs in a variable proportion of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It is more frequent and more serious in subjects from some ethnic/racial groups than in others.1 That is particularly the case for non-white patients, not only in the U.S. but also around the world.2 Often, patients with lupus nephritis (LN) do not respond adequately to the available treatments and go on to develop renal damage and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Despite significant advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of LN and tailored treatments to prevent these outcomes that have been or are being developed, many gaps in our knowledge and understanding of renal involvement still exist and deserve further investigation.

In this review, some of the many abstracts on research into LN presented at ACR Convergence 2025 are highlighted. The abstracts selected demonstrate the advances made on the early recognition of LN, as well as offering some hope in terms of achieving better outcomes, that is preventing the loss of renal function and the occurrence of ESRD and what that implies at the individual and societal levels in terms of quality of life, mortality and costs.3

The abstracts selected fall in different categories: markers of LN and the value of the so-called liquid renal biopsy, the value and need of a kidney biopsy to better guide the treatment needed and whether to perform it earlier than indicated in the 2024 ACR Guideline for the Screening, Treatment, and Management of Patients with Lupus Nephritis,4 the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), the factors contributing to the occurrence of ESRD and advances in treatment.

Urinary Biomarkers & a Liquid Renal Biopsy

Abstract 1480: Lee et al.5 & Abstract 0839: Jing et al.6

The aforementioned guideline established a urine-protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR) of ≥0.5 as the threshold to perform a kidney biopsy and proceed to implement treatment.4 Urinary biomarkers are useful in these patients, but could they also be useful in patients with lower levels of UPCR? This is the question posited by Lee and colleagues, authors of this multicenter U.S. study.

To this end, 21 patients with low proteinuria (and one indicator of the risk for the occurrence of LN: non-white race, low C3, low C4, anti-dsDNA positivity or an active urinary sediment), 282 patients with higher levels of proteinuria, and 31 healthy controls were included.

-

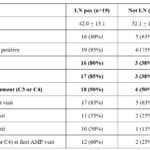

- Table 1: Patient Characteristics and Histopathologic Features at Time of Biopsy. # one patient had UPCR >0.5 at screening but 0.099 on repeat pre-biopsy.

-

- Figure 1: Urinary Biomarkers of Inflammation & Fibrosis Are Elevated in Early Lupus Nephritis Across ISN Classes.

The authors focused on the following eight biomarkers from a much larger panel: IL-16, CD-163, CD-206, PR3, Galectin-1, Tenascin-C, BAFF and C9. Of the 21 patients with low proteinuria, 13 had LN confirmed by biopsy: one with class I, four with class II, three with class III and five with class V. Table 1 (click the image to enlarge) shows the characteristics of these patients, whereas Figure 1 (click the image to enlarge) demonstrates the frequency distribution of these biomarkers in the patients studied and their higher values in patients with LN class III compared with the healthy controls, suggesting that proliferative LN is active at lower levels of proteinuria, with evidence of M1/M2 macrophage activation (CD163, CD206), B cell stimulation (BAFF), complement activation (C9), and fibrotic remodeling (Tenascin-C).

The data presented suggests that LN may be ongoing in patients with much lower levels of proteinuria and thus the current guideline may need to be modified. These data have applicability to the management of SLE patients at risk of developing LN.

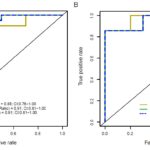

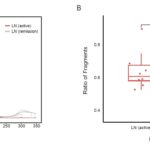

In the study by Jing et al. from Hong Kong, the role of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as a marker of LN was studied. To this end, 10 patients with active LN, seven with LN in remission, 13 patients with SLE but without LN >10 years post diagnosis and 10 healthy controls were studied. New methylation-based deconvolution methods were developed to quantify kidney-derived cfDNA and to differentiate active LN from remission (fragmentation patterns).

A clear differentiation between active and inactive LN was demonstrated with these deconvolution methods as shown in Figures 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B and 4 (click the images to enlarge).

-

- Figures 2A&B: Kidney-derived cfDNA levels measured by three deconvolution methods are significantly elevated in active LN patients. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

-

- Figures 3A&B: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of kidney-derived cfDNA levels profiled by NNLS, ReadsRatio and RPKM deconvolution algorithms distinguishing SLE patients with active LN from all other SLE patients (A) and SLE patients with active LN from those with LN in remission (B).

-

- Figure 4: cfDNA fragmentation pattern for identification of active LN patients (red) and inactive LN patients (Grey). Plasma cfDNA fragments of 30-157bp are enriched in active LN patients compared to inactive LN patients. ***P<0.001.

These studies are shedding additional light into the early events occurring in LN and whether the threshold to perform a kidney biopsy is adequate or should be modified. Earlier LN diagnosis may lead to the institution of adequate therapy earlier and thus prevent the occurrence of loss of renal function and of ESRD.

When to Perform a Renal Biopsy

Abstract 0772: Petri et al.;7 Abstract 0842: Fava et al.;8 & Abstract 0613: Kharouf et al.9

As noted, the 2024 ACR guideline indicates that a UPCR ≥0.5 is the threshold agreed upon to perform a kidney biopsy in patients with lupus.4 These three abstracts bring additional information to this contentious matter.

The first two abstracts included patients from different U.S. and non-U.S. academic centers, making the case for lowering this threshold so all patients with LN could be promptly diagnosed and receive proper treatment.

The third abstract is from Canada and addresses a different scenario: Can, under certain circumstances, a kidney biopsy not be done and the patient be treated based on the clinical information available?

In the first abstract, the authors strongly make the case for lowering the threshold to perform a kidney biopsy. This recommendation is based on finding that 20 of 28 patients in whom the biopsy was done at the lower threshold were found to have LN (two Class I, five Class II, six Class III and seven Class V); these patients were also more likely to have a history of a low C3 or a low C4 as shown in Table 2. In seven of the 20 patients with LN, the UPCR had progressed during follow-up despite treatment for Classes III and V.

In the second of these abstracts, 20 LN patients were included, and four urinary biomarkers were studied and related to histological LN activity at baseline (IL 16 and sCD163) and one year (tenascin-C and BAFF). These data suggest a temporal shift from macrophage-driven inflammation to stromal activation and B cell persistence in patients with LN. The authors emphasize the value of biomarkers as complementary tools that may allow a better characterization of what is going on in the kidneys in lupus patients. Figures 5 A-C (click the images to enlarge) depict the changes in renal histology class, lupus activity and chronicity.

In the Canadian abstract, a legit question is formulated: what to do when, for different reasons, a kidney biopsy can just not be done. To answer this question, the authors compared 43 patients with clinically diagnosed LN and 84 with biopsy-confirmed LN. Time to complete proteinuria recovery (CPR) at one year, progression to ESRD and a composite adverse outcome (i.e., infection, hospitalization or death) were the pre-defined established outcomes. Patients were treated with standard protocols. Over time, no differences in any of the three outcomes were observed between the clinically diagnosed and the biopsy-confirmed LN patients (Figures 6 A-C; (click the images to enlarge)).

-

- Figures 5 A-C: Patient demographics and histological features at baseline and one-year repeat biopsy. (A) Demographic and (B) clinical characteristics including ISN/RPS class, NIH Activity and Chronicity indices, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1). *Paired biopsies at 1 year were available for 18 patients: one biopsy was unsuccessful, and one patient declined repeat biopsy.

The authors emphasize that the intention of their study was not to dissuade practitioners from performing renal biopsies in their patients with SLE, but rather to assure them that in situations in which kidney biopsies cannot be performed, treated patients from this group may do as well as those in whom a biopsy was done.

Lupus Nephritis & How Frequently to Assess Proteinuria

Abstract 0837: Petri et al.10

The 2024 ACR guideline suggests that patients with lupus should be monitored for the development of proteinuria every six to 12 months.4 In this study encompassing 1,418 patients with lupus from the Hopkins lupus cohort, serial urine exams were conducted. The researchers concluded that such intervals are too long because proteinuria may occur de novo in these patients within a much shorter interval.

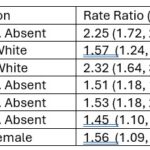

Different potential risk factors were examined and found to be associated with the occurrence of proteinuria, as shown in Table 3 (click the image to enlarge), namely non-white race, male gender, low C4 and anti-Sm, anti-dsDNA and anti-RNP antibodies. In addition, the greater the number of risk factors, the higher the probability of developing proteinuria as noted in Table 4 (click the image to enlarge).

-

- Table 3: Association Between Various Manifestations in the 1st Year After SLE Diagnosis & Eventual Incidence of Proteinuria

-

- Table 4: Risk of Incident Proteinuria Within 10 Years of SLE Diagnosis as a Function of the Number of Risk Factors.

These data strongly suggest that the current guidelines for the management of LN need to be modified if negative outcomes in these patients are to be prevented.

Lupus Nephritis in the Recent Era & Its Outcomes

Abstract 0638: Nakai et al.11 & Abstract 1522: Pena et al.12

A valid question is whether patients with LN fare better nowadays than they did in years past. This question was addressed in a study from Japan in which patients with recent-onset LN were compared with a historical cohort from the same center.

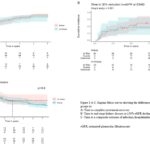

In this study, the authors concluded that, in fact, chronic kidney disease (CKD, stages 4 and 5), avascular necrosis and mortality have declined over time. Of interest, HCQ exposure was protective of the occurrence of CKD and of mortality as shown in Figures 7A and 7B (click the images to enlarge).

Figures 7 A&B: Hydroxychloroquine Prescription & Its Impact on Cumulative Incidence of CKD Stage 4 or 5 & All-Cause Mortality. (A) Hydroxychloroquine prescription and its impact on cumulative incidence of CKD stage 4 or 5. (B) Hydroxychloroquine prescription and its impact on cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality.

The second abstract refers to the role of HCQ in patients with LN who have undergone a renal transplant; to examine this, the authors compared transplanted LN patients who had received HCQ post-transplant with those who had not. To this end, the authors used the TriNetX database that includes patients’ data from 80 different global health organizations; they included 2855 SLE patients who had received HCQ post renal transplant and 4627 who had not. There were no differences in the occurrence of major cardiovascular events or cerebral infarction in the two groups, but there was a reduced risk of all-cause mortality in the HCQ group. However, the risk of progression to ESRD was higher in the HCQ group.

Taking the data from these studies together suggests that there is a role for the use of HCQ in patients with LN, but that careful follow-up and proper adjustments may need to be made along the way, particularly in the post-transplant LN patients. Properly conducted longitudinal studies may clarify these apparent inconsistencies.

The Role of Proteinuria Flares in Patients with LN

Abstract 1499: Petri et al.13

Approximately 20% of patients with LN progress to ESRD, with one well-established predictive factor being the occurrence of renal flares. In this study from the longitudinal Hopkins lupus cohort, paired visits (occurring less than 10 days apart and taken place after the renal biopsy had been done) were examined in 524 patients with SLE who had biopsy-proven LN. Predictive factors of a proteinuria flare were being African American, being young, having a low C3 and a lower household income. Serologies (low C3 and C4 and high anti-dsDNA antibodies), higher SLEDAI, a UPCR >500 mg and a higher serum creatinine were also predictors of a proteinuria flare. Most of these features made it into the multivariable model (Table 5; click the image to enlarge). In terms of medications, HCQ was not found to be protective, but ACE-inhibitor/ARB use were. Also of note, NSAIDs were found to be protective—a finding for which there is no clear explanation.

The authors emphasize the importance of preventing proteinuria flares because they are associated with progressive loss of renal function and the eventual occurrence of ESRD.

Advances in the Treatment of LN: Belimumab

Abstract 2439: Alomari et al.14 & Abstract 0642: Vidal Montal15

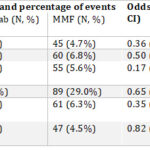

In the first of these abstracts, investigators compared belimumab (BEL) with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in patients with LN from the TriNetX network; they pulled the records of 1,052 patients with LN who had received BEL and 7,740 who had received MMF; patients receiving both were not included. After propensity score matching, 1,036 patients with LN remained in each group. Patients on BEL did better than those on MMF in terms of dialysis, renal transplant, hospitalizations and opportunistic infections. However, no differences were observed in terms of all-cause mortality, as shown in Table 6 (click the image to enlarge).

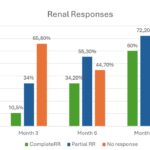

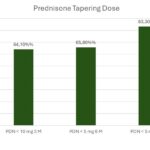

In the second of these abstracts, investigators from Spain examined renal outcomes and glucocorticoid tapering in 38 patients with SLE and proliferative LN [Class III (11 cases), Class IV (20 cases) or Class III/IV+V (seven cases)] who had been treated with triple therapy, which included BEL and standard of care. The goal was to determine renal response and glucocorticoid tapering in this real-world multicenter cohort. Figure 8 (click the image to enlarge) shows the renal response over time, whereas Figure 9 (click the image to enlarge) shows how the tapering of glucocorticoids in these patients was achieved.

Taken together, the data from these abstracts suggest that BEL is a reasonable choice for the management of patients with LN. It seems to be well tolerated, and its beneficial effects extend beyond the renal response because it allowed adequate tapering of glucocorticoids and the prevention of hospitalizations and opportunistic infections.

Advances in the treatment of LN: Obinutuzumab, Voclosporin & Tacrolimus

Abstract 0654: Vital et al.;16 Abstract 1546: Zala et al.;17 Abstract 1520: Toz et al.;18 Abstract 1521: Rovin et al.;19 & Abstract 1544: Sunkara et al.20

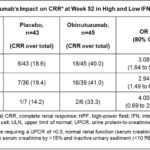

In the first of these abstracts, investigators examined various serological biomarkers in patients with LN from the phase 2 NOBILITY trial (obinutuzumab, OBI). One of these markers was interferon 1, whose status was examined using available gene signature data. Patients were divided into those with a high and low interferon signatures. Overall, OBI-treated patients did better than those in the placebo group; the response was more pronounced in those with a high interferon 1 signature. These data are depicted in Figure 10 and Table 7 (click the images to enlarge).

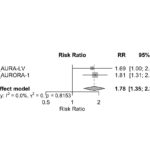

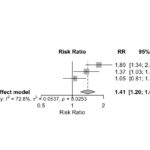

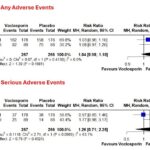

In the second abstract, the response to voclosporin (VOC) and tacrolimus (TAC) in patients with active LN was examined by conducting a meta-analysis. In all, five trials were included. In three of them, TAC was compared with conventional therapy (cyclophosphamide or MMF), and in two VOC was compared with a placebo control group in which all patients were on a background regimen of MMF and low-dose glucocorticoids. No differences in renal response were observed among patients in the TAC and VOC groups. The authors concluded that both are reasonable options for patients with active LN, as noted in Figure 11 (click the image to enlarge).

The next two abstracts deal with OBI; in the first of these, 26 patients with LN who had received OBI between 2015 and 2025 were included. Partial and complete renal responses were observed in 10 and eight patients, respectively, for a total overall response rate of 72%. Adverse effects were observed in 18 patients, but they were mostly mild or moderate. Some responder patients flared several years after a complete or a partial renal response had been achieved, as shown in Figure 12 (click the image to enlarge).

The second OBI abstract deals with data from the phase 3 REGENCY trial in which OBI showed superiority over placebo in terms of achieving a complete renal response at week 76. In this study, an unfavorable kidney outcome was defined as death or doubling of serum creatinine and treatment failure. Figures 13A and 13B (click the images to enlarge) demonstrate the superiority of OBI in terms of LN flare and unfavorable kidney outcome.

The final abstract in this group deals with the six-month and one-year efficacy data with VOC. Figures 14A and 14B (click the images to enlarge) demonstrate the complete renal response at six months and at one year, whereas Figures 15A and 15B demonstrate adverse events, any and serious, respectively. Overall, the data in this abstract supports the use of OBI in LN although caution should be exercised to monitor the occurrence of potentially serious side effects.

Taken together the data presented support the use of these new therapies for the management of patients with LN. Unfortunately, one of the main limitations for their use is their cost. This is even more of a case for low–middle income countries where these medications are not even available at the present, and it is hard to anticipate when they will be.21 Even if available, their cost may make them unreachable for the majority of patients for whom they may be indicated. Under these circumstances, following the 2024 guideline for LN management can be done by including only the more conventional treatments rather than these newer options.4

Is There a Role for GLP-1 in Lupus Nephritis?

Abstract 0841: Grzybowski a al.22

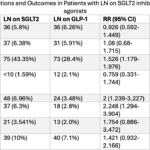

The anti-inflammatory properties of glucagon-like peptide are now very well recognized.23 The question these investigators posited is whether GLP use could be beneficial in patients with LN. To this end, they studied patients with LN who had received this compound and those who had received sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2). After propensity score matching, 694 patients remained in each group. Table 8 (click the image to enlarge) demonstrates the benefit of GLP-1 in terms of mortality, chronic kidney disease and major cardiovascular events.

-

- Table 8: Abbreviations: Acute MI: Acute Myocardial Infarction, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease, GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, LN: Lupus Nephritis, RR: Relative Risk, SGLT 2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval ; a- Propensity matched cohorts based on baseline demographics, comorbidities, and medication use. ; b- All patients with outcomes that occurred prior to the time window were excluded from our cohorts.

This compound, originally developed for the treatment of diabetes, may have an important role in the management of patients with LN. Further studies are needed, however, before this treatment is recommended.

Advances in the Treatment of LN: CAR T Cell Therapy

Abstract 2693: Nordmann-Gomes et al.;24 Abstract 2696: Morand et al.;25 & Abstract 269526

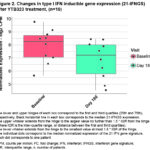

Although the review by Nordmann-Gomes et al. and the study by Morand et al. do not specifically address LN, I think they are worth mentioning given the efficacy of CAR T cell treatment in patients with severe, active and resistant-to-treatment SLE. A decrease in the SLEDAI from 12.8 at baseline to 2.3 at six months is noted in the first of these two abstracts and changes in type 1 interferon pathway and B cell depletion and repopulation with naive B cells are shown in the second of these abstracts (Figures 16 and 17; click the images to enlarge). When compared with other B cell-depleting treatments, such as rituximab and OBI, D19/CD3 T cell engager blinatumumab consistently produced full B cell-depletion as shown in Figure 18 (click the image to enlarge).

Taken together, these results cannot be considered other than superb and compelling, as noted by Nordman-Gomes at the meeting.

This new treatment modality, CAR T cell therapy, has brought numerous comments in the medical and non-medical literature around the world.26-30 At the present time, however, few places have implemented or can implement this treatment modality, and its cost may be prohibitive for most low–middle income countries.

Graciela S. Alarcón, MD, MPH, MACR, is the Jane Knight Lowe Chair of Medicine in Rheumatology (Emeritus), Department of Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine, Birmingham, Ala., and professor emeritus, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Perú.

References

- Musa R, Rout P, Qurie A. Lupus nephritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- Garg S, Sweet N, Boderman B, et al. Multiplicativity impact of adverse social determinants of health on outcomes in lupus nephritis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2024;76:1232–1245.

- Thompson JC, Mahajan A, Scott DA, Gairy K. The economic burden of lupus nephritis: A systematic literature review. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;9:25–47.

- 2024 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the screening, treatment and management of lupus nephritis. ACR Convergence. Washington D.C. 2024 Nov 18.

- Lee C, Lu R, Guthridge C, et al. Urinary biomarkers detect proliferative lupus nephritis in SLE patients with subclinical proteinuria [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Jing Q, Li Q, Chan C, et al. Precision liquid biopsy for lupus nephritis: cfDNA methylation and fragmentomic signatures enable non-invasive diagnosis and dynamic disease tracking [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Petri M, Fava A, Atta M, et al. Redefining when to biopsy the kidney in patients with SLE [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Fava A, Lee C, Guthridge C, et al. Association of urinary biomarkers with histological features in diagnostic and per-protocol repeat kidney biopsies in lupus nephritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Kharouf F, Mehta P, Li Q, et al. A baseline kidney biopsy is not always feasible in incident lupus nephritis: Insights from an inception cohort [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Petri M, Demirayak I, Fava A, et al. Risk of new proteinuria in next ten years in SLE [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Nakai T, Fukui S, Ikeda Y, et al. Prevalence of lupus nephritis, end stage kidney disease, avascular necrosis, and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus in the recent era [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Pena C, Tan I, Ali R, et al. Outcomes of continuing hydroxychloroquine following renal transplant in patients with lupus nephritis: A retrospective cohort study using the TrinetX database [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Petri M, Fava A, Goldman D, Magder L. Predictors of proteinuria flares in biopsy positive lupus nephritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Alomari A, Shah N, Rodriguez M, Alawneh D. Belimumab versus mycophenolate mofetil in lupus nephritis: A real-world comparative analysis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Vidal Montal P, Narváez J, Fabregat A, et al. Belimumab-based triple therapy in proliferative lupus nephritis: Renal outcomes and glucocorticoid tapering in a real-world multicenter cohort [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Vital E, Vargas B, Rae J, et al. Obinutuzumab shows promise in lupus nephritis regardless of baseline serological markers: An exploratory post hoc analysis of a phase ii trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Zala U, Patel R. Tacrolimus versus voclosporin for active lupus nephritis: A comparative meta-analysis of renal response [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Toz B, Vashistha H, Furie R. Long-term effects of obinutuzumab on kidney function in lupus nephritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Rovin B, Pendergraft W, Lightstone L, et al. Kidney-related outcomes with obinutuzumab in patients with active lupus nephritis: A pre-specified exploratory analysis of the clinical trial data [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Sunkara S, Medarametla R, Kotha M, Jarjour W. Voclosporin in lupus nephritis: Meta-analysis of 6-month and 1-year efficacy with 1-year safety outcomes [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Mendoza-Pinto C, Etchegaray-Morales I, Ugarte-Gil MF. Improving access to SLE therapies in low and middle-income countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 Mar 29;62(Suppl 1):i30–i35.

- Grzybowski K, Tan I. Comparing the impact of GLP-1 agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors on outcomes in lupus nephritis: A retrospective cohort study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Rabbani SA, El-Tanani M, Kumar R, et al. Repurposing diabetes therapies in CKD: Mechanistic insights, clinical outcomes and safety of SGLT2i and GLP-1 RAs. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025 Jul 28;18(8):1130.

- Nordmann-Gomes A, Khalili L, Tang W, et al. CAR T-cell therapy in SLE: A systematic review [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025;77(suppl 9).

- Morand E, Cortés-Hernández J, Amoura Z, et al. Biomarker data from an open-label, phase 1/2 study for YTB323 (rapcabtagene autoleucel, a rapidly manufactured CD19 CAR-T therapy) suggest reset of the B cell compartment in severe refractory SLE [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Tur C, Eckstein M, Bucci L, et al. B-cell depletion and lymphoid follicle disruption upon different B-cell depleting agents [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol.2025;77(suppl 9).

- Agrawal N. A cutting-edge cancer therapy offers hope for patients with lupus. The New York Times. 2025 Jul 18.

- Wang Q, Xiao ZX, Zheng X, et al. In vivo CD19 CAR-T cell therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. New Eng J Med. 2025 Oct 16;393(15):1542–1544.

- Grieshaber-Bouyer R, Schett G. CAR-T cells: Gaining a better understanding of treating lupus. Friedrich Alexander Universität, Erlangen-Nürnberg. 2025 Mar 20.

- Gever J. Potentially groundbreaking CAR-T product shows early promise in lupus. Novel method transforms patients’ T cells in vivo. MedPage Today. 2025 Sep 17.