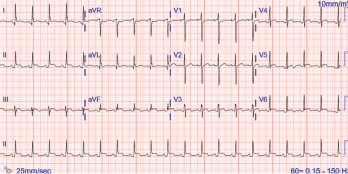

Figure 1. The ECG shows widespread ST elevation, along with PR segment deviation more prominent in leads I, II, AVF and AVR, suggestive of acute pericarditis.

The incidence of drug-induced lupus continues to rise as clinicians expand their therapeutic armamentarium. An estimated 15,000–30,000 cases of drug-induced lupus occur every year in the U.S. alone.1 It is a well-known, but rare, complication of commonly used medications, such as anti-hypertensive, anti-arrhythmic and anti-epileptic drugs, as well as biologic and immune checkpoint therapies.2,3

The mechanism of how drugs cause this autoimmune phenomenon is only partially understood. The complex disease pathophysiology includes such factors as the host’s acetylator status, alterations in innate and adaptive immunity, certain drugs acting as haptogens and the generation of cytotoxic metabolites, which result in an autoimmune reaction, often causing detrimental effects on the target organs.4-6 The most common presenting symptoms of drug-induced lupus overlap with idiopathic systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). These include fever, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue and musculoskeletal symptoms.7 However, the multi-organ manifestations seen in idiopathic SLE are uncommon in drug-induced lupus.

Given the lack of diagnostic criteria, clinicians often rely on the identification of a temporal relationship between administration of the drug and the development of symptoms for diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old Black woman with a history of epilepsy who had taken phenytoin and topiramate for seven years presented to our hospital with a one-month history of intermittent, sharp, substernal chest pain and progressive exertional dyspnea. She denied experiencing fever, cough, flu-like symptoms, leg swelling, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, oral ulcers, hair loss, skin rash or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

She had visited two different urgent care facilities prior to this presentation and was prescribed over-the-counter analgesics. On arrival, her blood pressure was 120/73 mmHg, her pulse was 98 beats/minute, her temperature 36.5ºC, and she had a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/minute with normal saturation on ambient air. She had trace pedal edema with decreased breath sounds bilaterally, but an otherwise normal systemic examination.

Complete blood counts revealed a white blood cell count of 5.9×103 cells/μL (normal: 4.5–11.0×103 cells/μL), hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL (normal: 11–13.5 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 81.9 fL (normal: 81–99 fL) and platelets of 369×103 cells/μL (normal:150–400 x103 cells/μL). Her inflammatory markers were elevated: erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 65 mm/hr (normal: 0–20 mm/hr) and a C-reactive protein of 30.93 mg/dL (normal: <0.5 mg/dL). Her troponin I was elevated at 1.8 ng/mL (normal: <0.03 ng/mL). She had normal renal and liver functions.

An evaluation for anemia revealed a ferritin level of 82 µg/mL (normal: 11–307 µg/mL), total iron binding capacity of 210 µg/dL (normal: 284–507 µg/dL), transferrin saturation of 6% (normal: 15–50%) and an iron level of 13 mcg/dL (normal: 50–212 mcg/dL). Her serum lactate dehydrogenase was 317 U/L (normal: 140–271 U/L). Her reticulocyte count, peripheral smear and haptoglobin levels were unremarkable.

Her electrocardiogram showed diffuse ST segment elevations with PR segment depressions suggestive of acute pericarditis (see Figure 1).

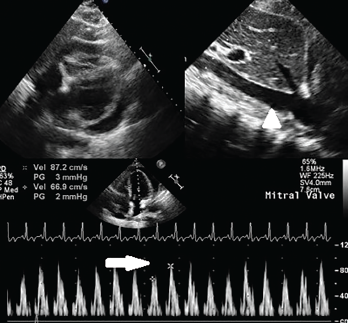

Figure 2. A circumferential pericardial effusion with collapsing RV chamber in early diastole, along with dilated IVC (arrowhead); inflow variation approximately 25% across the MV is suggestive of tamponade physiology (arrow). Key: RV = right ventricle; MV = mitral valve

A chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly. An initial echocardiogram showed moderate circumferential pericardial effusion with normal ejection fraction of 55% and no regional wall motion abnormalities. Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) of the thorax confirmed a large pericardial effusion, without any mediastinal or parenchymal mass and minimal bibasilar atelectasis.

The patient was initiated on 0.6 mg of colchicine twice daily and 800 mg of ibuprofen three times daily. On the third day, a serial echocardiogram showed worsening pericardial effusion, with the presence of tamponade physiology that warranted urgent pericardiocentesis; 400 mL of serosanguinous pericardial fluid was drained (see Figure 2).

On analysis, the fluid was exudative, with high numbers of neutrophils. The pericardial fluid protein level was 6.8 g/L, and the LDH was 2,088 U/L. A gram stain was negative; subsequent cultures and cytology were also unrevealing. Autoimmune serologies revealed a positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2,560 (normal: <1:20), anti-dsDNA antibody of 1:320 (normal: <1:20), P-ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) of 1:5,120 (normal: <1:20), anti-histone antibodies of 9.2 IU/mL (normal: <1.0 IU/mL) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) ANCA IgG titer of 39 AU/mL (normal: <19 AU/mL). Other serologies were unremarkable (see Table 1). Tests for Coxsackievirus A and B, tuberculosis and HIV were also negative (see Table 1).

Table 1: Autoimmune Serological Markers

| Autoimmune Panel | Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) | 1:2,560 | <1:20 |

| Anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies | 1970-01-01 06:20:00 | <1:10 |

| Anti-histone IgG antibodies | 9.2 units | <0–0.9 units |

| Anti-SSA (Ro) IgG antibodies | 63 AU/mL | <29 AU/mL |

| Anti-SSB (La) IgG antibodies | 5 AU/mL | <29 AU/mL |

| Anti-Sm/RNP complex antibodies | 40 AU/mL | <29 AU/mL |

| Anti-smith IgG antibodies | 5 AU/mL | <29 AU/mL |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (P-ANCA) | 1:5,120 | <1:20 |

| Anticardiolipin IgG antibodies | 13 GPL | 0–14 GPL |

| Anti-b2glycoprotein IgG antibodies | 5 SGU | 0–20 SGU |

| Lupus anticoagulant | Undetected | |

| Myeloperoxidase antibody IgG | 39 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| Serine proteinase 3 AB IgG | 5 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| ACE | 3 U/L | 9–67 U/L |

Given the elevated troponins and concern for myopericarditis, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and showed nonspecific, acute pericarditis with moderate, complex pericardial effusion, but no evidence to suggest myocarditis.

Discussion

The distinction between drug-induced lupus and idiopathic SLE is clinically important because the prognosis of the former is usually favorable when the drug is withdrawn. In addition to the temporal relationship, which may be difficult to ascertain because symptoms may develop years after a drug exposure, several other factors help clinicians implicate a certain drug as the trigger for drug-induced lupus.8,9 These include cessation of the lupus-like symptoms within weeks to months of discontinuing the drug therapy, lack of clinical or laboratory evidence of idiopathic SLE prior to initiation of drug therapy, and the presence of anti-histone antibodies with low titers of anti-dsDNA antibodies.

The drugs implicated in inducing lupus can be categorized in terms of their risk or probability of causing lupus: high (>5%), moderate (1–5%), low (0.1–1%) or very low (<0.1%).2,7 Phenytoin carries a very low risk of generating autoimmunity, but it has been postulated to cause immune reactions that have resulted in skin manifestations, nephritis, pericarditis and ANCA-associated vasculitis from hypersensitivity reactions with multi-organ involvement.10-14

In general, anti-epileptic drugs have been found to modulate immune system activity by affecting humoral and cellular immunity. The role of cellular or innate immunity in the form of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) has gained much interest in recent years in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.7 These web-like structures formed by neutrophil cell death, termed NETosis, comprise nuclear and cytosolic proteins extruded in response to various sterile and non-sterile stimuli. NET contents include double-stranded DNA, histones, proteinase 3 and MPO, which are the main targets of autoantibodies detected in ANCA-associated vasculitis, SLE and drug-induced lupus. Enhanced NET formation has been previously demonstrated with certain drugs, such as carbamazepine and hydralazine.15

The distinction between drug-induced lupus & idiopathic SLE is clinically important because the prognosis of the former is usually favorable when the drug is withdrawn.

Our patient had strongly positive ANA, positive anti-histone, positive anti-SSA, and anti-dsDNA antibodies with low titers, along with positive MPO-ANCA. We hypothesize that overproduction of NET could be one mechanism to explain the presence of multiple antibodies caused by phenytoin in our patient. However, the rationale for a very late presentation remains unclear because additional immunogenic triggers and susceptibility factors may have played a role.

The development of drug-induced lupus after several years of exposure to anti-epileptic agents, such as carbamazepine and phenytoin, has been previously described in the literature.10-14 The responsible antibodies directed against histone proteins are present in over 75% of patients with drug-induced lupus, but are also found in 25–50% of patients with idiopathic SLE. Antibodies to double-stranded DNA are detected in under 5% of patients with drug-induced lupus and are often present in low titers. In addition, the co-positivity of anti-MPO antibodies with ANA has also been strongly associated with drug-induced lupus, compared with idiopathic SLE or ANCA-associated vasculitis.16

Our patient had no manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis, a bland urinalysis, normal renal function, and no skin or pulmonary features.

Cardiac involvement in lupus may manifest with pericarditis or pericardial effusion, myocarditis, conduction system defects, valvular pathologies and coronary artery diseases. Pericardial involvement resulting in cardiac tamponade is rare.17 In a combined series of approximately 1,500 patients with SLE, tamponade was reported in fewer than 1–2.5%, an association that is scarce even with drug-induced lupus.18,19

The rare occurrence of tamponade as the initial manifestation of drug-induced lupus has been described previously in a few case reports, more so with carbamazepine.20 Previously, a case of fulminant myopericarditis secondary to phenytoin use was reported by Atwater et al.8

Our patient did not have features of myocarditis, with a normal ejection fraction, absence of regional wall motion abnormalities and lack of myocardial involvement on MRI. However, she developed echocardiographic tamponade requiring urgent pericardiocentesis. In the absence of active infection, no evidence of a malignancy by fluid analysis and imaging, and positive autoimmune serologies without characteristic SLE or vasculitis features, an eventual diagnosis of drug-induced lupus from phenytoin was made.

Phenytoin was gradually tapered off, with substitution of levetiracetam. Our patient did not require the addition of steroids or hydroxychloroquine during hospitalization or upon discharge. She had normalization of inflammatory markers with no recurrence of pericardial effusion on follow-up after three months, with tapering of ibuprofen and colchicine.

Conclusion

Cardiac tamponade secondary to phenytoin-induced lupus is an extremely rare phenomenon. Early recognition of such an association may be challenging after years of drug exposure and with abrupt onset of the disease.

Haseeb Chaudhary, MD, is a chief resident in internal medicine at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System, Pennsylvania, and a rheumatology fellowship candidate.

Haseeb Chaudhary, MD, is a chief resident in internal medicine at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System, Pennsylvania, and a rheumatology fellowship candidate.

Prem Parajuli, MD, is a hospitalist at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System.

Prem Parajuli, MD, is a hospitalist at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System.

Devy Setyono, MD, completed a rheumatology fellowship at Wake Forest Medical University, Winston-Salem, N.C. She is currently in practice at Emkey Arthritis & Osteoporosis Clinic, which is affiliated with Tower Health System.

Devy Setyono, MD, completed a rheumatology fellowship at Wake Forest Medical University, Winston-Salem, N.C. She is currently in practice at Emkey Arthritis & Osteoporosis Clinic, which is affiliated with Tower Health System.

References

- Borchers AT, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Drug-induced lupus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Jun;1108:166–182.

- Arnaud L, Mertz P, Gavand PE, et al. Drug-induced systemic lupus: Revisiting the ever-changing spectrum of the disease using the WHO pharmacovigilance database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr;78(4):504–508.

- Kosche C, Owen JL, Choi JN. Widespread subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a patient receiving checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Oct 15;25(10):13030/qt4md713j8.

- Cameron HA, Ramsay LE. The lupus syndrome induced by hydralazine: A common complication with low dose treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984 Aug18;289(6442):410–412.

- Batchelor JR, Welsh KI, Tinoco RM, et al. Hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus: Influence of HLA-DR and sex on susceptibility. Lancet. 1980 May 24;1(8178):1107–1109.

- Speirs C, Fielder AH, Chapel H, et al. Complement system protein C4 and susceptibility to hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 1989 Apr 29;1(8644):922–924.

- Vaglio A, Grayson PC, Fenaroli P, et al. Drug-induced lupus: Traditional and new concepts. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Sep;17(9):912–918.

- Atwater BD, Ai Z, Wolff MR. Fulminant myopericarditis from phenytoin-induced systemic lupus erythematosus. WMJ. 2008 Sep;107(6):298–300.

- Pelizza L, De Luca P, La Pesa M, Minervino A. Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus after 7 years of treatment with carbamazepine. Acta Biomed. 2006 Apr;77(1):17–19.

- DeFelice T, Lu P, Loyd A, et al. Livedo racemosa, secondary to drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2010 Nov 15;16(11):24.

- Parry RG, Gordon P, Mason JC, Marley NJ. Phenytoin-associated vasculitis and ANCA positivity: A case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996 Feb;11(2):357–359.

- Kheir F, Daroca P, Lasky J. Phenytoin-associated granulomatous pulmonary vasculitis. Am J Ther. 2016 Jan–Feb;23(1):e311–e314.

- Gaffey CM, Chun B, Harvey JC, Manz HJ. Phenytoin-induced systemic granulomatous vasculitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986 Feb;110(2):131–135.

- Siragusa RJ, Ramos-Caro FA, Edwards NL. Drug-induced lupus due to phenytoin. Journal of Pharmacy Technology. 2000 Jan 1;16(1).

- Irizarry-Caro JA, Carmona-Rivera C, Schwartz DM, et al. Brief report: Drugs implicated in systemic autoimmunity modulate neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Mar;70(3):468–474.

- Cambridge G, Wallace H, Bernstein RM, Leaker B. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in idiopathic and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994 Feb;33(2):109–114.

- Stevens M. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the cardiovascular system: The heart. In: Lahita R, ed. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992:707–717.

- Kahl LE. The spectrum of pericardial tamponade in systemic lupus erythematosus: Report of ten patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1992 Nov;35(11):1343–1349.

- Maharaj SS, Chang SM. Cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015 Mar 17;13(9).

- Verma SP, Yunis N, Lekos A, Crausman RS. Carbamazepine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as cardiac tamponade. Chest. 2000 Feb;117(2):597–598.