The effects of knee osteoarthritis (OA) on an individual can go far beyond having to live with a stiff and painful knee. People with symptomatic knee OA are less active than their peers and are at increased risk for inactivity-related diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Inactivity produces general deconditioning as well as increased pain, weakness, stiffness, and functional loss. Knee OA is a major cause of disability, and prolonged inactivity adds to the loss. Fortunately, many of the sequelae of knee OA are modifiable through exercise.

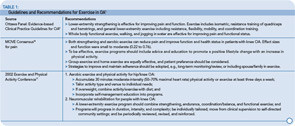

As shown in Table 1, guidelines for the management of hip and knee OA consistently recommend exercise as an integral component of management.1 Both strengthening and aerobic exercises show positive results in clinical trials. Outcomes of exercise include decreased pain and improved function as well as increased strength, range of motion, and cardiovascular health. It appears that moderate exercise does not increase the incidence or speed progression of the disease and there is emerging evidence that regular moderate exercise can reduce effusions and improve the content of glycosoaminoglycans in cartilage, an important biochemical indicator of its viscoelastic properties.2,3 Aerobic walking, stationary cycling, strengthening, and water exercise are all safe and effective for patients with OA. Whether the exercise is performed at home, in a clinic, or in a group setting, benefits are clear, with generally moderate effect sizes in this diverse population.

Despite the well-documented evidence for the numerous benefits of regular exercise for people with knee OA, most people with this condition are nevertheless inactive and receive little information or support from physicians on how to be physically active. There are understandable reasons for this inattention to a known, effective intervention. Pain usually prompts the doctor visit and immediate treatment focuses on pharmacologic pain relief. Time and resources to prescribe appropriate exercise and follow-up are limited in most clinical encounters. Furthermore, the general nature of exercise recommendations in medical guidelines, the range of possible activities, and the diversity in this patient population make it difficult for the physician to know what to recommend. Although well-intentioned, the suggestion to “start getting some exercise” is not particularly helpful or often followed.

However, we know that physicians and clinic staff can influence patients to change beliefs and behaviors in areas such as smoking cessation, diet, and exercise.4 With knowledge and planning, it is possible—within the constraints and staffing of the clinic visit—to establish procedures to help patients become more active and exercise successfully. Here is a useful framework for how to: 1) promote awareness of the importance of exercise at the time of the office visit; 2) offer a simple home exercise program; 3) use community-based exercise and self-management resources; and 4) identify patients to refer to physical therapy.

Promote Exercise at the Office Visit

In general, people who receive advice from their physician to exercise are more likely to exercise than people who do not. People with arthritis who exercise often begin because a physician suggested it and provided information. In a study of rheumatologists and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, only 58% of the physicians discussed exercise with their patients, and most physicians reported that they did not have the time or feel comfortable recommending exercise.5 To follow current management guidelines for knee OA, exercise should be discussed at every office visit. It is up to the physician to start the discussion.

Ask every patient at every visit: What are you doing for exercise now?

Your response depends upon the patient’s answer:

- If the activity lies within the exercise guidelines for fitness or the physical activity guidelines for general health (see Table 3) reinforce and encourage the activity.

- If your patient answers that he or she is not doing anything but would like to do something, or if what the patient is doing is inadequate, refer him or her to a community-based exercise or self-management program or suggest a home program. (Click here to download a sample home exercise program.)

- If your patient answers that he or she cannot exercise because of pain, is afraid to try, or exhibits the signs or symptoms listed in Table 2, consider referral to a physical therapist to help him or her overcome barriers and learn how to exercise successfully. Also, suggest a community arthritis-specific exercise program or self-management program for continued use and support.

Table 4 outlines the role of the healthcare professional in promoting exercise and the characteristics of a successful exercise program.

Exercise Starts at Home

Many people with mild to moderate knee OA can lessen pain and improve function and endurance with a simple home exercise program. Studies reporting successful home exercise interventions usually include initial instruction and supervision. The Enabling Self-management and Coping with Arthritic Knee Pain through Exercise (ESCAPE) trial also includes self-management training in the initial six-week period.6

Offering specific suggestions of safe and effective activities may help some patients get started. Basic strengthening and flexibility exercises, combined with a progressive program of regular walking or bicycling are a simple, no-cost routine that can be accomplished at home. (Click here to download a sample home exercise program.) Combining a beginning home program with referral to a self-management course helps the person learn skills, experience success, and develop self-efficacy for exercise, thereby improving adherence and outcomes.

Evidence-based Community Resources

Learning the self-management skills for self-directed exercise is central to long-term exercise maintenance.7 There are a number of community-based opportunities that offer initial instruction, access to a knowledgeable leader, and social support to gain these skills. The Arthritis Foundation and CDC-supported state Arthritis Programs are excellent sources of evidence-based programs. These programs have been shown to improve symptoms, reduce disability, and promote self-efficacy for managing the disease. The self-management programs include exercise information and teach skills that foster self-directed behaviors and success. Learn what is going on in your area, keep course information available in your office, and refer patients to these programs as standard care. The evidence-based programs recommended and supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Arthritis Program are Arthritis Foundation Exercise Programs—Land and Water; Arthritis Self- Management Program; Chronic Disease Self-Management Program; and Enhance Fitness. More information about these exercise and self-management programs may be found at the following sites:

- Arthritis Foundation Chapter programs: www.arthritis.org/programs.php;

- CDC State Arthritis Program: www.cdc.gov/arthritis/state_programs/programs/index.htm;

- Enhance Fitness, a senior exercise program developed by the University of Washington: www.projectenhance.org; and

- A list of self-management programs, including chronic disease, offerings in Spanish, and international locations: http://patienteducation.stanford.edu.

Local hospitals, recreation centers, and fitness facilities offer exercise programs suitable for people with arthritis. Water aerobics, low-impact aerobic dance, cycling, strengthening, and tai chi are safe and helpful. Your own patients are a good source of information on what works, what doesn’t, and where to find good instructors and classes. Encourage patients to share experiences with you and your staff. It can be efficient to designate a specific staff member to be the knowledgeable exercise resource and talk with patients and families regularly.

Most people with mild to moderate knee OA can exercise successfully in a community-based program or on their own if the physician initiates discussion of the importance of physical activity, offers positive recommendations and follows up consistently. People who have more severe disease or worse symptoms may initially need more arthritis-specific instruction and supervision to learn how to exercise without increasing pain or becoming discouraged. People who attribute their activity limitation to arthritis and are currently not engaged in a regular physical activity program often will do better in group classes that address arthritis issues and self-management training. However, people for whom current pain is severe or for whom minimal activity increases pain may benefit from a more individualized therapeutic encounter.

Some Patients Benefit from Physical Therapy

A referral to physical therapy is appropriate if your patient is limited by pain, has a history of unsuccessful exercise attempts, exhibits gait deviations, or exhibits marked weakness or malalignment of the knee (i.e., laxity or varus or valgus deformity) or malalignment of the foot/ankle (e.g., ankle/foot pain, uneven shoe wear). A physical therapist can offer evidence-based care and assist the person with knee OA in a number of areas.8 Table 4 lists common problems that limit a person’s ability to be physically active that can be addressed by a physical therapist.

Summary

Patients are more likely to follow an exercise program if it is introduced by the physician and reinforced regularly at office visits. If the physician expresses interest, engages in discussion, offers positive suggestions, and promises to follow up on subsequent visits, the patient is more likely to attempt the activity. It is not necessary for the doctor to be an exercise specialist or have all the answers, but it is critical to express interest in what the patient is doing, be positive in your belief in the importance and feasibility of increasing patient activity, and suggest resources and make appropriate referrals. With exercise as a foundation of OA management, outcomes should improve as patients become stronger and more active and their pain and disability diminish.

Dr. Minor is professor and chair of physical therapy at the School of Health Professions at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

References

- Westby MD, Minor MA. Exercise and physical activity. In Bartlett SJ, ed. Clinical Care in the Rheumatic Diseases. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals; 2006:211-219.

- James MJ, Cleland LG, Gaffney RD, Proudman SM, Chatterton BE. Effect of exercise on 99mTc-DTPA clearance from knees with effusions. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:501-504.

- Roos EM, Dahlberg L. Positive effects of moderate exercise on glycosaminoglycan content in knee cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3507-3514.

- Rapoff MA, Bartlett SJ. Adherence in children and adults. In Bartlett SJ, ed. Clinical Care in the Rheumatic Diseases. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals; 2006: 279-284.

- Iversen MD, Fossel AH, Ayers K, et al. Predictors of exercise behavior in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 6 months following a visit with their rheumatologist. Phys Ther. 2004;84: 706-716.

- Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell HL, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a rehabilitation program integrating exercise, self-management, and active coping strategies for chronic knee pain: A cluster randomized trial. Arth Rheum. (Arth Care Res.) 2007;57:1211-1219.

- Brady TJ, Boutaugh ML. Self-management education and support. In Bartlett SJ, ed. Clinical Care in the Rheumatic Diseases. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals; 2006: 203-210.

- Jamtvedt G, Dahme KT, Christie A, et al. Physical therapy interventions for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: An overview of systematic reviews. Phys Ther. 2008; 88:123-135.

- Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis. i. 2005;85:907-971.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: The MOVE consensus. Rheumatology. 2005;44:67-71.

- Work Group Recommendations: 2002 Exercise and Physical Activity Conference, St. Louis, MO. Session V: Evidence of benefit of exercise and physical activity in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (Arth Care Res.) 2003; 49:453-454.

- Franklin BA, Whaley MH, Howley ET. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6th ed. Philadephia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.