VEXAS has a heterogenous presentation and many potential hematologic and inflammatory aspects, including persistent elevation of inflammatory lab markers. Among the most common disease features outlined in the guidance document are dermatologic symptoms, such as neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), auricular or nasal chondritis, ocular involvement witsh periorbital swelling, groundglass or nodular pulmonary infiltrates, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thromboembolic disease and fever of unknown origin.

However, patients may also have less common inflammatory-type symptoms, with involvement of the peripheral nervous system, heart, kidneys and/or other types of skin manifestations.

“It’s really about understanding some of the particular features of the disease,” says Dr. Koster. “Not all patients are going to have auricular or nasal chondritis, for example, but if you have an older man with auricular or nasal chondritis, you need to have VEXAS in the differential.”

Macrocytic anemia is very commonly, but not universally, present, especially in the earliest stages of the progressive disease. Dr. Koster also highlights the possibility of monocytopenia, an unusual finding in the setting of many other rheumatologic diseases, which often display a reactive monocytosis instead. Thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia can also occur, as can vacuoles in early erythroid or myeloid precursor cells on bone marrow aspirate.

Some of these patients have previously received a rheumatic diagnosis, such as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) vasculitis or relapsing polychondritis. However, these patients usually have very atypical presentations, and they are often glucocorticoid-dependent and poorly responsive to standard treatments.

Management of VEXAS

A key thrust of the guidance document is the need for collaboration in both diagnosing and managing such patients. “It’s really a team-based approach, with rheumatologists and hematologists as two of the most important coordinators,” says Dr. Koster. “It’s critical to have both perspectives because rheumatologists are not as comfortable with cytopenias, and hematologists are not as comfortable with managing and monitoring inflammatory states.”

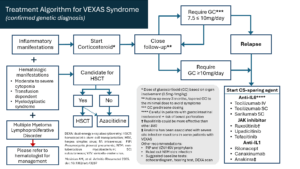

Disease activity in VEXAS can be defined by inflammation or worsening bone marrow failure. Treatment (see Figure 1) must encompass controlling inflammation, treating bone marrow failure and addressing any secondary complications from treatment (e.g., glucocorticoid toxicities).

Clinicians should start glucocorticoids for all patients with confirmed VEXAS and inflammatory manifestations. Glucocorticoid-sparing agents can be added as well, with some small studies and experience at expert centers showing potential benefits for anti-interleukin (IL) 6 or anti-IL-1 therapies, or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. These agents, targeting inflammatory pathways, appear to be more effective than conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs or B cell-directed therapies. Although many centers are using anti-IL-6 agents as the first-line therapy, not enough evidence exists to establish that definitively.