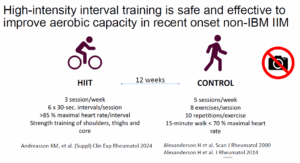

CHICAGO—According to speakers in a presentation at ACR Convergence 2025, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has been shown to be safe and have multiple health benefits—including improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, immune function and disease activity—for those with inflammatory diseases. Speakers outlined these impacts and discussed how to best integrate HIIT into a person’s treatment plan.

“HIIT is realistic for most of our patients because intensity can be personalized to individual fitness levels,” said Kim Huffman, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C. “In patients with inflammatory arthritis, this intervention not only shows excellent improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness, but also inflammatory disease activity and self-reported outcomes such as fatigue.”

HIIT can take many forms. For example, Dr. Huffman recruited 12 older adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) for a pilot study. Over 10 weeks, they walked on a treadmill for 30 minutes, three times a week. Participants performed up to 90 seconds of high intensity exercise on the treadmill followed by a similar amount of time of active recovery at moderate to low intensity.1

Scores Improved

What surprised the researchers was improvement in disease activity scores. Those in high disease categories went to moderate, with other categories behaving similarly. Some even went into remission. They found the participants’ cardiorespiratory fitness (e.g., maximum oxygen consumption measured as peak VO2 in a cardiopulmonary exercise test) improved as well.

Dr. Huffman’s group showed that changes in systemic oxidative capacity from HIIT were highly associated with improvements in CD4+ T-cells oxidative capacity, and generated more naive CD4+ cells.

RA Not the Only Disease HIIT Effects

A combination of HIIT, aerobic training and resistance training resulted in lowered disease activity, increased fitness and positive changes in other areas in additional types of inflammatory arthritis, including psoriatic arthritis.2 Patients with psoriatic arthritis participated in three-times-weekly HIIT-based cycling with a control group that did not change its exercise regimen. There were no statistically significant between-group differences, but in the HIIT group, fatigue improved. In both groups, disease activity improved. Interestingly, the control group had better pain control.3

There is a dose-dependent relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality. There is also evidence that those with inflammatory diseases have greater risk for cardiovascular disease. HIIT addressed this concern as well.

In patients with inflammatory arthropathies at risk for cardiovascular events, HIIT led to health improvements. Compared to usual care controls, the group that participated in twice-weekly supervised and once-weekly unsupervised training saw improved fitness and disease activity within the HIIT group. However, there were no changes in cardiac metabolic risk factors.