Using this system, patients are screened for both red and yellow flags. Red flags are associated with serious medical conditions that can mask as musculoskeletal pain (see Table 1).10-12 Yellow flags are believed to represent psychological barriers that may delay recovery.

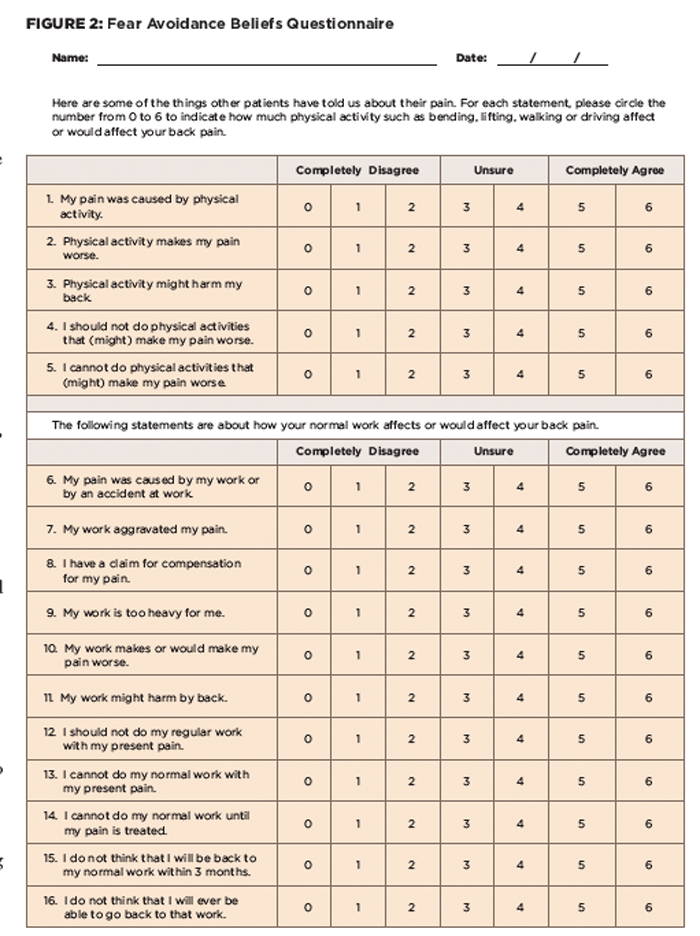

According to Fritz and colleagues, “fear-avoidance beliefs [see Figure 2] are present in patients with acute LBP, and may be an important factor in explaining the transition from acute to chronic conditions.”13-15 Fear-avoidance beliefs are established early in the course of a pain experience and serve no protective purpose.15 Many believe that fear-avoidance beliefs, specifically about work, are the psychosocial factors that could best be used to predict return to work in patients with acute work-related LBP.13-15

There is strong evidence that once a worker has been out of work for four to 12 weeks, they have a 10–40% risk (depending on the setting) of remaining off work at least one year. After one to two years’ absence, it is unlikely they will return to any form of work, irrespective of further treatment.15

(click for larger image)

Figure 2: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

This screening is typically done during initial physical therapy evaluation, but can also be done by the primary care provider (see Table 2).

Although patients with LBP are commonly referred to physical therapy, the referral is often delayed. A number of studies have shown that early access to physical therapy (within 30 days) by patients with LBP actually improved patient outcomes. Early access was associated with decreased utilization of advanced imaging, decreased additional physician visits, and fewer surgeries, injections and opioid medications.16-20

After information is gathered from self-reported measures, the history and a thorough physical examination, patients are allocated into one of four subgroups: manipulation, stabilization, specific exercise (flexion, extension and lateral-shift patterns) and traction. Each subgroup is named for the primary treatment that the patients would receive once assigned.

TBC Category 1: Manual Therapy Subgroup

This subgroup is believed to respond favorably to manipulation and/or mobilization of the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint. Evidence suggests that patients who fall into this subgroup generally have a shorter duration of symptoms (<16 days), at least one level of hypomobility (segmental stiffness) of the lumbar spine and symptoms that don’t extend beyond the knee.21

A prospective, cohort study by Flynn et al was carried out with the objective of developing a clinical prediction rule (CPR) to identify patients with non-specific LBP who would improve with spinal manipulation. The CPR includes five variables (see Table 3); when four of these five variables were present, patients were very likely to improve (positive likelihood ratio, 24), increasing the probability of success with manipulation from 45–95%, and the presence of two or fewer variables was almost always associated with a failure to improve (negative likelihood ratio, 0.09). This CPR has been validated by a randomized controlled trial.22

There is strong evidence that once a worker has been out of work for four to 12 weeks, they have a 10–40% risk (depending on the setting) of remaining off work at least one year. After one to two years’ absence, it is unlikely they will return to any form of work, irrespective of further treatment.

Many commentators continue to believe that there is a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of manual treatment (spinal manipulation/mobilization) on LBP.23 However, most studies have not used homogenous samples, and thus, patients who may indeed benefit by spinal manipulation/mobilization are grouped with others who likely would not benefit. Researchers are now challenging this myth with subgrouping methods to maximize treatment outcomes.