During a cold spell in the winter, a 58-year-old woman came into our rheumatology clinic complaining of discomfort from cold hands. She said that the problem started in 2004 when she was 53 years old; she gave an otherwise negative medical history (see Figure 1). She did not have symptoms related to any connective tissue disease, and her physical exam was unremarkable. There was no sclerodactyly, pitting scars, or dyspnea. Lung function analysis did not show signs of restrictive lung involvement (total lung capacity 99%, vital capacity 113%, diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide [DLCO] 109%). At echocardiography, there were no signs of abnormal pulmonary function (systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 25 mmHg). The laboratory showed low positivity for antinuclear antibodies (dilution 1:80), with immunofluorescence staining indicating a centromere pattern; immunoassay showed positivity for anticentromere antibodies.

Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon or Systemic Sclerosis?

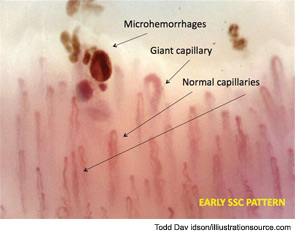

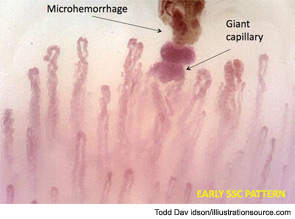

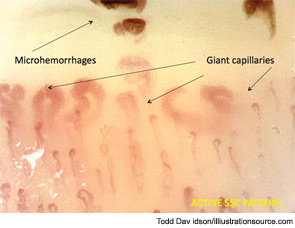

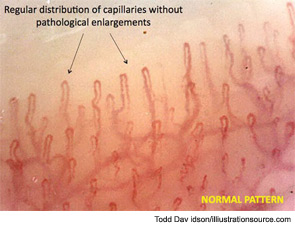

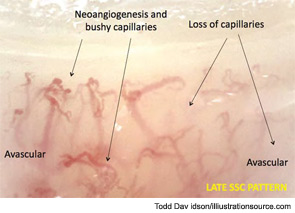

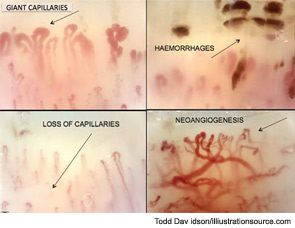

Further evaluation of the patient by nailfold videocapillaroscopic (NVC) analysis demonstrated the combination of giant capillaries and microhemorrhages, an “early” scleroderma pattern (see Figure 2). Since these findings are characteristic of microvessel damage in systemic sclerosis (SSc), the diagnosis turned to secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 In this case, the diagnosis of early SSc was based on the criteria of LeRoy and Medsger, which were recently validated and include the scleroderma pattern by NVC and the presence of specific autoantibodies.2,3