Presentation

The majority (60%) of patients are diagnosed before the age of 18 and are identified because of a positive family history.24 Early presenting features in children include excessive bruising, thin, translucent skin showing visible venous patterns, and congenital abnormalities, such as clubfoot and hip dislocation.25 Patients may also display characteristic facial features, which include the presence of prominent eyes (owing to lack of lack of subcutaneous adipose tissue around the eyes), a thin, pinched nose, small lips, hollow cheeks and lobeless ears.

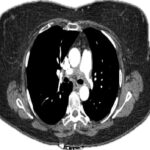

Complications are overall rare in childhood, but up to 25% of patients may experience their first major event by the age of 20 and 80% by the age of 40.26 The majority of complications are arterial in nature and consist of aneurysm formation, dissection or rupture of medium-sized vessels. The most frequently involved sites include the abdominal visceral arteries, iliac arteries and thoracic and abdominal aorta.27 Abdominal visceral aneurysms or dissections often involve multiple visceral arteries. The next most frequent locations of arterial involvement include carotid, subclavian, ulnar, popliteal and tibial arteries.28 Most patients will develop multiple vascular complications without any antecedent trauma, which may be symptomatic or discovered incidentally.34

Gastrointestinal complications occur in up to 25% of patients, with spontaneous rupture of the sigmoid colon being the most common complication.25,28 In the 30-year Mayo Clinic experience, the reported survival free from an arterial, intestinal or uterine complication was 84% at age 20, 37% at age 30 and only 4% at age 60. This highlights the risk of patients with the condition developing devastating complications over time.28

Differential

The differential diagnosis for SAM and vEDS is broad because many vasculopathies demonstrate similar radiologic findings. The differential includes atherosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), infections (e.g., mycotic aneurysm and endocarditis), small-to medium-sized vasculitides (e.g., ANCA-associated vasculitides and polyarteritis nodosa), connective tissue diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus and Behçet disease) and inherited defects in vessel wall structured proteins (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan’s syndrome).29

Most cases can be excluded on clinical grounds, and laboratory studies are typically normal in terms of inflammatory markers and autoimmune serologies in patients with SAM. FMD can be difficult to differentiate from SAM because the conditions are both non-inflammatory, non-atherosclerotic arterial diseases with similar histologic and angiographic findings.30–33 However, the clinical profiles differ, with FMD occurring in mainly in young to middle-aged women who may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms associated with occlusive disease and rarely rupture. The pattern of arterial involvement is also different with FMD in which the renal and internal carotid arteries are most affected. Extrarenal visceral involvement is considered less common in FMD as well, in contrast with SAM where the converse is true.5,8,12,34