Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil; HCQ) has been an important and effective drug for the treatment of lupus erythematosus and related autoimmune and inflammatory diseases for half a century, although its potential to cause retinal damage continues to raise concern among rheumatologists and ophthalmologists. Further, despite the overall safety profile of HCQ, some patients with preexisting vision problems (e.g., glaucoma, cataracts) may be reluctant to take a medication with any potential for ocular toxicity, thus depriving them of a valuable therapy.

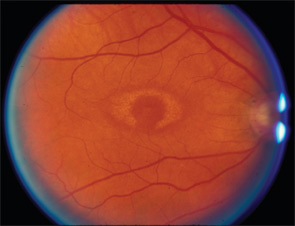

It is important to know the facts. Retinal complications from HCQ are actually rare (at proper dosage) and, with good screening, the risk for visual loss is very low. Nevertheless, retinopathy begins to appear with long-term use, and retinopathy is serious insofar as there is no known treatment. It can progress for a year or more after stopping the drug and, if not recognized early (at the point of screening), it can lead to functional blindness. The classic clinical picture of HCQ toxicity is a “bull’s eye” maculopathy (see Figure 1)—but as I’ll later note, this is a late finding.

Data on retinal complications associated with HCQ and recommendations for screening for HCQ toxicity from the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) have been published recently, and they have important clinical and legal implications for the rheumatologist.1,2 This article is intended to highlight new knowledge about how this toxic effect develops and can be recognized.

TABLE 1: Ideal Weight

Women: 100 lb + 5 lbs per inch over 5 ft

Men: 110 lb + 5 lbs per inch over 5 ft

Incidence

The best data on HCQ toxicity are from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.1 They suggest that, in an unselected population, the risk is below 1% for toxicity within the first five to seven years of treatment as long as dosage is within general guidelines. However, frequency of toxicity rises thereafter, probably reaching several percentage points by 15 to 20 years of use, although there were not enough cases in the data bank to give a firm number. From anecdotal data and the large number of overdose cases among published reports of toxicity, the risk is clearly accelerated and higher with overdose. Further, the recognition of toxicity may rise with the use of more sensitive diagnostic tools for screening. I have seen a dozen cases of toxicity in the past year, which is rather high for a suburban area, even when considering referral patterns.

Daily Dose

The new AAO recommendations focus more on the duration of treatment rather than a daily dose but emphasize that overdosage is dangerous.2 Most patients receive two tablets (400 mg) per day, which is fine for women taller than 5 ft. 7 in. or men taller than 5 ft. 5 in. Why is height important? Because the drug does not distribute in fatty tissues, so an “ideal” weight is a critical parameter for dose calculation. Many of the overdose cases I have seen have received dosage by weight, and these patients were overweight. The ideal weight formula is show in Table 1.

Short patients should have a dosage calculated by the traditional 6.5 mg/kg using ideal weight. Keep in mind that because of the slow action of the drug, intermediate doses can be achieved easily by variable intake (e.g., 300 mg/day is gained by alternating one and two pills on successive days).

Duration of Use

After five to seven years of HCQ use, the risk of retinal toxicity is above 1%, and the AAO recommends annual screening. This screening might begin earlier or occur more often in patients at unusual risk because of renal or liver disease (slower clearance), old age (harder to assess macular changes), underlying retinal disease, and other factors. Toxicity is rare under 1,000 gm of cumulative dosage (or about 16 gm/kg ideal weight). The higher these figures grow, the greater the risk. There are many patients with 25 years of HCQ use and no evidence for toxicity, but the longer the drug is used, the greater the likelihood of toxicity, making proper screening more critical.

Screening for Toxicity

Screening is necessary because the off-center (bull’s eye) pattern of early damage means that most patients keep good central vision initially and don’t notice the development of toxicity. Thus, counseling patients about the risk for toxicity and the need for screening is important when starting HCQ. Although patients should be aware of the need for good quality annual screens, much of the practical responsibility falls on the physician who sees the patient on a regular basis—to remind patients of the importance of screening or to refer appropriately. Many of the cases of toxicity that I see were missed initially because of irregular or poor screening. Screening cannot prevent toxicity, but it can catch it early enough to prevent a loss of visual acuity.

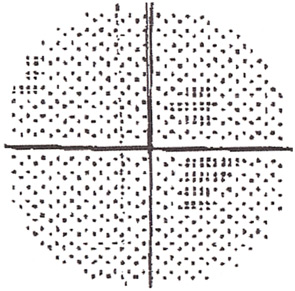

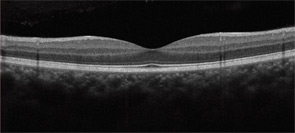

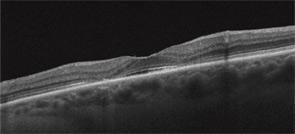

The new AAO recommendations make some important changes in the prior advice on how to screen. First, the subjective tests, such as the Amsler grid and automated visual fields, are recognized as variable in value because of variable performance—not only of the patient, but also of the doctor who may assume that a few “errors” are just noise in the test. Amsler grids (handheld grid patterns) are no longer acceptable because their results vary too often, and automated 10-2 visual field testing (i.e., field testing the central 10 degrees of vision) is accepted only with the proviso to be very alert with HCQ patients and retest if any new areas of sensitivity loss appear (see Figure 2). The new AAO recommendations also emphasize that ophthalmoscopic examination for “bull’s eye retinopathy” (see Figure 1) is not a screening test; fundus changes appear too late and represent retinal damage of such longstanding duration that the underlying retinal pigment epithelium cells have also degenerated.

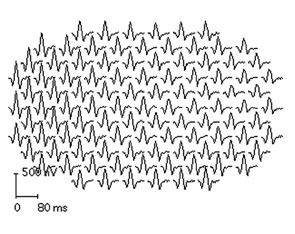

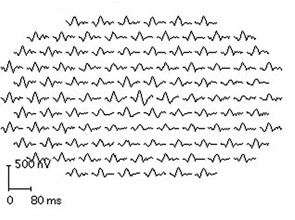

Second, it is strongly recommended that newer objective tests be used routinely. In practical terms, high-resolution, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) is widely available in many retina specialty practices and some general ophthalmology offices and appears to be more sensitive than fields. (Older time-domain OCT units do not have sufficient resolution for screening.) SD-OCT is an imaging technique that creates an optical cross-section of the retina and visualizes early damage from the drug as thinning in the parafoveal region (see Figure 3). The multifocal electroretinogram (mfERG) tests electrical function of the retina topographically across the macula; in essence, it is an objective visual field (see Figure 4). It is highly sensitive like the SD-OCT but not so readily available. Fundus autofluorescence is also objective but still is under evaluation for sensitivity.

Bottom Line

It is not adequate just to send patients off to the local optometrist or ophthalmologist for screening for HCQ toxicity unless that eye specialist is aware of the new AAO guidelines and has the means to obtain (where possible) an SD-OCT or mfERG test.2 Also, a baseline retinal exam is advised within the first year after a patient starts the drug to assess any underlying maculopathy. This is critical because underlying maculopathy can confuse later assessment of toxicity and become a relative contraindication to using the drug.

HCQ retinopathy is, sadly, very much alive and well. Much of the responsibility for informing patients and initiating screening falls on rheumatologists because they are usually the primary doctor initiating use of the drug. The patient is at risk—and the physician is at risk medicolegally—if adequate screening is not performed. Although the AAO recommendations represent guidelines, they are often recognized as a standard of care. The key points to remember are the following:

- Don’t overdose—400 mg/day is too much for short individuals, using ideal weight.

- Obtain a baseline eye exam, and start annual screening after five years.

- Be aware that longer use increases the risk.

- Be aware that effective screening now should include at least one objective test (such as SD-OCT). Do not rely on observation of the retina for screening, and be wary of visual field testing unless done by a practitioner attuned to look for early and subtle changes.

Dr. Marmor is professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, Calif.

References

- Wolfe F, Marmor MF. Rates and predictors of hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:775-784.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TYY, Lyons JS, Mieler WF; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Revised recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: Ophthalmology. 2011;118:415-422.