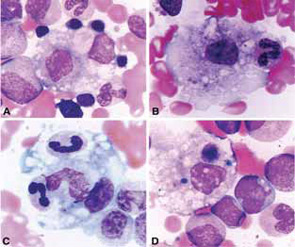

The hemophagocytic macrophages in MAS express CD163.16,17 This feature provides clues to the understanding of the origin of extreme hyperferritinemia in MAS. The only proven function of CD163 is related to its ability to bind hemoglobin– haptoglobin complexes and initiate pathways important for the adaptation to oxidative stress induced by free heme and iron (see Figure 2, p 29).18 In these pathways, to prevent cell damage caused by iron-derived reactive oxygen species, free hemoglobin, the main source of redox-active iron, forms a complex with haptoglobin. The haptoglobin–hemoglobin (Hp–Hb) complexes then bind to CD163 and are internalized by the macrophage. Endocytosis of Hp–Hb complexes leads to upregulation of heme oxygenase (HO) enzymatic activity. HO degrades the heme subunit of Hb into biliverdin, which is subsequently converted to bilirubin, carbon monoxide and free iron. The free iron is either sequestered in association with ferritin within the cell or transported and distributed to red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow. Increased uptake of Hp–Hb complexes by macrophages leads to increased synthesis of ferritin. In MAS, increased release of free Hb associated with erythrophagocytosis would require increased production of ferritin to sequestrate an excessive amount of free iron. Indeed, a strikingly high level of serum ferritin (often above 10,000 ng/dL) is an important diagnostic feature of both MAS and HLH.

Clinical Features

The clinical findings in overt MAS are often dramatic and evolve rapidly. Typically, patients with a chronic condition become acutely ill with persistent fever, mental status changes, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver dysfunction. A hemorrhagic syndrome resembling disseminated intravascular coagulopathy is another striking feature of MAS. Hemorrhagic skin rashes from mild petechiae to extensive ecchymotic lesions, epistaxis, hematemesis secondary to upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and rectal bleeding, are commonly seen in these patients. These clinical symptoms are associated with a precipitous fall in at least two of three blood cell lines (leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets). The fall in platelet count is usually an early finding. Because bone marrow aspiration typically reveals significant hypercellularity and normal megakaryocytes, such cytopenias do not seem to be secondary to inadequate production of cells. Increased destruction of the cells by phagocytosis and consumption at the inflammatory sites are more likely explanations.