Back Pain

Stanton TR, Henschke N, Maher CG, et al. After an episode of acute low back pain, recurrence is unpredictable and not as common as previously thought. Spine. 2008;26:2923-2928.

Abstract

Study Design: Inception cohort study.

Objective: To provide the first reliable estimate of the one-year incidence of recurrence in subjects recently recovered from acute nonspecific low back pain (LBP) and to determine factors predictive of recurrence in one year.

Summary of background data: Previous studies provide potentially flawed estimates of recurrence of LBP because they do not restrict the cohort to those who have recovered and are therefore eligible for a recurrence.

Methods: We identified 1,334 consecutive patients who presented to primary care with acute LBP; of these 353 recovered before six weeks and entered the current study. The primary outcome measure was recurrence of LBP in the next year. Specifically, an episode of recurrence was defined in two ways: recall of recurrence at the 12-month follow-up and report of pain at the three- or 12-month follow-up. Risk factors for recurrence were assessed at the baseline. Pain intensity was assessed at six weeks, three months, and 12 months and recurrence at 12 months. Factors that could plausibly affect recurrence were chosen a priori and evaluated using a multivariable regression analysis.

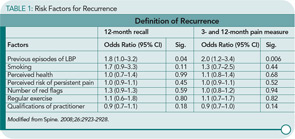

Results: Recurrence of LBP was found to be much less common than previous estimates suggest, ranging from 24% (95% CI=20–28%) using “12-month recall” definition of recurrence, to 33% (95% CI=28–38%) using “pain at follow-up” definition of recurrence. However, only one factor, previous episode(s) of LBP, was consistently predictive of recurrence within the next 12 months (odds ratio=1.8–2.0, P=0.00–0.05)

Conclusion: This study challenges the assumption that the majority of subjects with low back pain whose symptoms resolve will have a recurrence in a one-year period. After the resolution of an episode of acute LBP, about 25% of subjects will have a recurrence in the next year. Prediction of who will have a recurrence within the next year is difficult to determine.

Commentary

An acute episode of back pain is one of the most common afflictions of mankind. Studies have reported wide variations in the numbers of individuals who have experienced this malady. Seemingly, at one time or another, more people than are the world’s population have experienced pain in the area below the 12th rib and the crease of the buttocks. Although having one attack is bad enough, patients with back pain are at risk of a recurrence. Reports of the frequency of recurrences have ranged from 47% to 84% depending on the study population. An explanation for the wide range in the frequency of recurrences may be related to the definitions of recurrence. These definitions have been variously based upon pain, use of healthcare, or absence from work. For example, van den Hoogan et al reported a 75% recurrence rate based upon pain in 443 LBP subjects who responded to a postal questionnaire at 12 months.1 While relapses were less severe and of shorter duration than the initial episodes, no specific factors that predicted recurrence were identified in this study.

In response to these variances in definitions of recurrence, the investigators from Australia designed this study to answer the questions of the frequency of recurrence and the risk factors for developing recurrent episodes. A subject eligible for the study had an episode of pain for at least 24 hours but less than six weeks in the lumbar region and was preceded by a period of at least one month without back pain. The date of recovery was defined as the first day of a pain-free period of one month. Participants were asked about the development of pain at three months and 12 months and recall of back pain of at least 24 hours’ duration at 12 months. Baseline characteristics of the patients were obtained for multivariate analysis to identify factors predictive for recurrence.

Of an inception cohort of 1,334 patients with acute LPB, 353 recovered by the six-week follow-up. An interesting finding of the study that is not discussed is the almost 1,000 individuals with LBP who did not have a resolution of symptoms at six weeks. The exclusion of these individuals did not have an effect on the study results since the goal of the current study was the frequency of recurrence not the natural history of LBP recovery. Excluding these individuals affirmed the study group to be homogenous in having LBP that resolved in a timely fashion. The one-year incidence of recurrence based on recall at 12 months was 24%. When using pain assessments at three and 12 months, the one-year incidence of recurrence of LBP increased to 38%. An impressive component of the study results was the 100% follow-up rate over a 12-month period. A list of the factors examined for risk of recurrence is shown in Table 1, below. Of all the factors listed, an episode of back pain prior to entrance in the study was the sole factor with predictive value.

Overall this study has good and not-so-good news for individuals with LBP. This study offers some good news for individuals with an episode of LBP in that only about a quarter of individuals will have a recurrence of pain over a subsequent 12-month period. This recurrence rate is one of the lowest reported in medical literature. These findings pertain to individuals who are in their mid 40s and who have soft tissue problems of the lumbar spine. It does not pertain to individuals with herniated discs or spinal stenosis. The disheartening news is that LBP is the gift that keeps on giving. If you have had it once, you are at risk for a subsequent attack just because you had a previous attack. This is part of the story that cannot be modified to decrease risk. This study tells us that the best way of preventing recurrences is to prevent LBP episodes in the first place. In an attempt to decrease the risk of LBP episodes in individuals, I recommend core strengthening exercises to build up paraspinous and abdominal muscles. Using proper lifting techniques such as facing the object and using leg power can avoid the twisting injury that can be the cause of a sustained LBP episode

I do believe that individuals who have had one episode of back pain are at risk for another. Many patients try to get back to their baseline level of activity too quickly. I recommend that they start back with exercise in a gradual program. Patients should start at one-tenth of the activity level and gradually increase exercise (walking, stationary bike) over time as postexercise soreness remains minimal. I encourage them to attempt to reach a reasonable body weight gradually over time. I limit the use of braces because they can result in diminished muscle tone in the lumbar spine muscles.