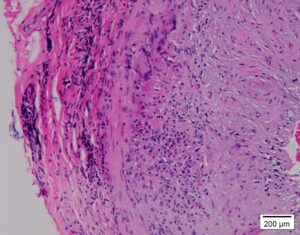

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), is an inflammatory vasculitis that involves large- and mediumsized arteries, most commonly the cranial branches of the carotid artery.1 It is seen in individuals 50 years and older.1 The most typical manifestation is new-onset headache with scalp tenderness and jaw claudication. 2 The most feared complication associated with GCA is permanent visual loss; therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are essential.2 High levels of acute phase reactants are seen in patients with GCA, and diagnosis is usually confirmed by a temporal artery biopsy.3

The following case describes the rare finding of scalp necrosis in a patient with GCA.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a headache and new-onset, left-side, peripheral vision loss associated with jaw claudication and unintentional weight loss. Two weeks before, he had fallen and hit his head. He then developed scalp lesions on the left side, with progression to the right side, as seen in Figures 1 and 2.

The patient underwent brain imaging, which was unrevealing. He was seen by an ophthalmologist the day prior to admission and that exam noted left, optic disc edema, with visual field defect.

Given these findings, there was concern for GCA, and tests for erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were ordered.

On exam, ulcerated scalp lesions were visualized, and the patient was started on valacyclovir to cover the possibility of herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

In the emergency department, the patient’s vitals were stable. Ulcerated scalp lesions were noted on both the right and left sides of his head. He also had tenderness on palpation of the left temple. Laboratory tests were significant for leukocytosis (white blood cells of 17,800 cells/mm3; reference range [RR]: 4–10,500 cells/mm3) and elevated inflammatory markers: an ESR of 26 mm/hr (RR: 0–20 mm/hr) and a CRP of 23.1 mg/L (RR: <10 mg/L).

The patient was seen by a physician in the infectious disease and dermatology department who did not feel his lesions were consistent with herpes zoster.