CHICAGO—At a session of ACR Convergence 2025, attendees absorbed key insights into the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Two experts on JIA coordinated the joint lecture: pediatric rheumatologist Evelyn Rozenblyum, MD, FRCPC, and adult rheumatologist Natasha Gakhal, MD, FRCPC, MSc, both of Women’s College Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada.

Together, Dr. Rozenblyum and Dr. Gakhal founded and co-lead a JIA young adult clinic at Women’s College Hospital, a clinic in which interprofessionals, and pediatric and adult rheumatologists collaboratively manage young adults aged 17– 25 and help meet this population’s special needs as they transition to adult care.

Becoming an Adult Patient

The majority of pediatric patients with JIA will eventually require adult care, noted Dr. Rozenblyum, and many still have a high burden of disease during this transition. Of patients with active disease, the vast majority require therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) into adulthood.

Dr. Rozenblyum noted that, for a variety of reasons, many young adults with JIA fail to successfully transition to adult care. “It’s important that we think about thoughtful ways to prepare them for transition from pediatric to adult care within the healthcare system,” she said.

It’s also critical to address psychosocial issues in young adults with JIA because they navigate not just their disease, but also new challenges of moving through the adult world, some of which directly affect their healthcare options and their overall health and wellbeing. In some reports, young adults with JIA tend to have worse educational and vocational outcomes, especially if their disease is uncontrolled, Dr. Gakhal said.

Providers should not just ask about symptoms related to disease activity, but also about mood, education and vocation, substance use and pregnancy considerations. “First and foremost, we should control their disease, but we can also connect them with resources,” Dr. Gakhal said.

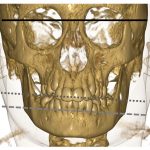

Dr. Rozenblyum and Dr. Gakhal also discussed uveitis and arthritis of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), two aspects of care with ongoing questions and implications in this young adult population with JIA.

Clinical Pearls in Uveitis

About 10–30% of JIA patients develop uveitis. Dr. Rozenblyum noted this is usually an asymptomatic chronic anterior type of uveitis, different from most presentations in adult rheumatology.1 If not addressed, such uveitis can lead to such complications as synechiae (i.e., adhesion of the papillary muscles due to inflammation), cataracts, glaucoma and vision loss. Because it is usually asymptomatic, screening becomes even more important.