Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most used drugs for acute and chronic pain. More than 30 billion doses of NSAIDs are consumed annually from more than 70 million prescriptions.1

Despite their common use, NSAIDs are not free of serious toxicities. In the pre-Vioxx (rofecoxib) era, gastrointestinal toxicity was the primary concern for many NSAIDs. In 1999, Wolfe et al. demonstrated the increasing rate of hospital admissions due to NSAID toxicity, thought mostly to be due to gastrointestinal (GI) side effects.2,3

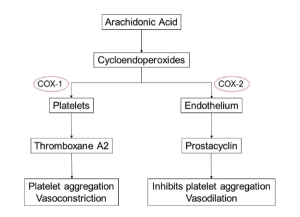

This led to the development and use of selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX‑2) inhibitors, the first of which was celecoxib, released in 1998, followed soon by rofecoxib in 1999 and several others.4,5 These agents had no effect on COX-1, an enzyme responsible for production of cytoprotective prostaglandin E2 and I2 in the stomach and, hence, had reduced risk of GI side effects.6

An exponential rise in the use of these drugs occurred.5 Simultaneously, strong evidence demonstrating that many of these agents confer a risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and other cardiovascular events developed.

The Mechanism of NSAID Cardiovascular Risk

The relation of MI risk and COX-2 inhibition is most noted in a study conducted by Garcia-Rodriguez et al.7 They noted a direct correlation between MI risk and the degree of COX-2 over COX-1 inhibition. The exact mechanism of COX-2 inhibition remains unknown, but the hypothesis of an imbalance between thromboxane

A2 (which promotes platelet aggregation and acts as a vasoconstrictor) and prostacyclin (an inhibitor of platelet aggregation and a vasodilator), produced by both platelets and endothelial cells, has gained the most prominence.8-10

Similarly, it has been postulated that reduced prostaglandin synthesis due to NSAID use augments the Th-1 mediated immune response, which leads to increased proatherogenic cytokines. This ultimately leads to detrimental plaque remodeling, rupture and embolization of plaque.11

Researchers think the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis increases peripheral vascular resistance and reduces renal perfusion, glomerular filtration and sodium excretion, which would ultimately lead to fluid retention and further contribute to the cardiovascular toxicity.11

More than 88,000 Americans suffered myocardial infarction due to rofecoxib, & more than 38,000 died.

Myocardial Infarction

The Downfall of COX-2 inhibitors Selective inhibitors of COX-2 came under closer scrutiny after two landmark trials, the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research study and the Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) studies.12,13 Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular events, which led to the withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market in 2004. It was subsequently estimated that more than 88,000 Americans suffered myocardial infarction due to this drug, and more than 38,000 died.