In 1905, two pediatricians in Vienna, Austria, published Serum Sickness, a detailed 120-page monograph that was the first to carefully characterize the syndrome.1 The work would go on to become a classic, ultimately helping illuminate many important questions in immunology.

Antitoxin Serum Treatments

In the late 19th century, researchers were working to develop lifesaving antitoxins to certain bacterial diseases.2 Scientists learned how to harvest toxins from bacteria grown in a laboratory. They would then inject horses or other animals with the toxin, and the animals’ immune systems would produce an antitoxin. This could then be collected from the animals, purified and administered as a serum. The antitoxin could successfully neutralize the effects of the original bacterial toxin, such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae.3

Tetanus antitoxin was discovered in 1890, and the first case of diphtheria treated with antitoxin was described the following year.2 Such antitoxins soon became common in clinical practice. Clinicians could treat infected persons with them or use them prophylactically in some situations, such as to control disease outbreaks. Anti-serum injections of C. diphtheriae gave patients immunity for around three weeks.4

Dr. Atkinson

According to John P. Atkinson, MD, the Samuel B. Grant Professor of Medicine at Washington University, St. Louis, School of Medicine, “It was pre-antibiotics. Initially this was the only treatment that had been shown to be effective.”

Quickly, it was recognized that though they could save lives, antitoxin serums sometimes caused side effects. Rarely, rapid anaphylactic-type responses were observed after a person was injected with serum.

But another type of response was almost universally observed, initially termed serum exanthema. These self-limited responses were not life threatening and were deemed relatively insignificant. However, the process of coming to understand these responses would contribute to a wider understanding of many important processes in immunology.1,5

Die Serumkrankheit (Serum Sickness)

From 1903 to 1910, Viennese pediatrician Clemens Freiherr von Pirquet, PhB, MD, made very detailed and important observations that helped provide foundational work for the fields of immunology and allergy.5 The studies put forth in Die Serumkrankheit were key components. He wrote the monograph in collaboration with Béla Schick, MD, a Hungarian-born pediatrician with whom he worked at the University of Vienna as lab assistant to Theodore Escherich (known for his work on Escherichia coli).6

Dr. Pirquet

Arthur M. Silverstein, PhD, an immunologist, science historian and professor emeritus of ophthalmic immunology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, says, “It really was a phenomenal, remarkable piece of work.”

“It is beautifully done,” Dr. Atkinson adds. “It’s very logical and thought provoking and has great attention to detail. You read paragraph after paragraph about issues that came up: How much serum was administered and where, which disease was being treated, patients’ ages, how sick they were, the timing of everything. All these things were carefully documented in what we might call a long clinical article.”

The pair became the first to describe the syndrome in detail and the first to propose that serum sickness arose as a product of an immunological process.5

Clinical Description

The first part of the monograph, “Clinical Aspects of Serum Sickness,” makes up more than half of the text. Here, Pirquet and Schick explored the nature of symptomatology and disease course, referencing case studies of adults and children gathered in their clinic work. They provided detailed graphs showing the timing of specific clinical symptoms as well as laboratory findings, such as leukocyte numbers and blood precipitins.

At the outset, they renamed the syndrome. They wrote:

We have abandoned the expression ‘serum exanthema’ because we think that this name could easily lead to the idea that the rash was the most important symptom of the disease; in its place we have proposed the name ‘serum disease’ or ‘serum sickness.’

Pirquet and Schick were careful to document timing in patients who had never been exposed to anti-sera before:

Most frequently the symptoms of disease start suddenly between 8 and 12 days after the injection … . The period of incubation cannot be explained by the slowness of the absorption of the foreign serum. This serum exerts its anti-toxic effect within a few hours.

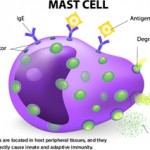

Dr. Atkinson confirms this timing coincides with what we now know about antibody production. “It takes humans five or six days to make antibodies. The IgM comes up, and a few days later the IgG comes up. Then it interacts with the horse serum—immunoglobulin and other proteins, depending on how clean and pure it was. Depending on the ratios and the precipitation reaction, it can form immune deposits in the kidneys and in the joints. Then, as you clear it out within a couple of days, it all goes away.

“The rash and fever were two of the most common problems,” adds Dr. Atkinson. “They described the fevers, how high they were and how long they lasted. Quite a few patients got joint pains, and they go through which joints, whether symmetrical or non-symmetrical. They mention that a few patients had albuminuria.” The pair also noted such symptoms as enlarged lymph nodes and edema, which they documented carefully through tracking patients’ weights.

Pirquet and Schick also made key insights into the relationship of serum dosage to symptom onset, noting:

The intensity of the symptoms also becomes decidedly stronger with an increase in the amount of serum … . The prophylaxis of serum sickness consists in the first place in using the smallest possible amount of serum.

Readministration

In the second section of the monograph, Pirquet and Schick carefully documented the differences in patients receiving a second dose of serum. They observed a large group of children who received diphtheria anti-sera due to exposure on a clinical ward. They then noted the differences between children who had previously received injections and those who had not. Those who had been reinjected often showed an accelerated response, sometimes within 24 hours. They wrote:

This difference could not be due to the antigen (injected serum), as we have shown in our experiments, since the same serum caused different kinds of differently timed reactions, depending on whether it was injected into the organism for the first time or was reinjected. Thus we came to the conclusion that it was the human organism which has become specifically altered, due to the injection of a foreign serum.