‘Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) is a bit of a headscratcher because it can mimic any number of other conditions,’ says Physician Editor Bharat Kumar, MD, MME, FACP, FAAAAI, RhMSUS. ‘Luckily, new insights empower diagnosis and management so we can help manage this great mimic.’

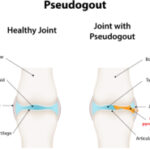

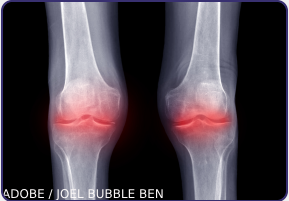

The fourth most common type of arthritis in adults has a well-deserved reputation as a medical chameleon. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease, as its name implies, is a form of arthritis caused by the deposition of tiny calcium pyrophosphate crystals in the cartilaginous tissue of joints around the body. Unlike most other rheumatological diseases, CPPD is a relative newcomer in the medical literature, with the first description appearing in 1962.1 So far, researchers don’t know exactly why the crystals precipitate in some people and not others, although the disease mostly affects individuals older than 60.

CPPD can present as either an acute or chronic disease, and to the consternation of rheumatologists, it often takes the guise of other conditions. “I always think about CPPD as the great mimicker of diseases that we see in the rheumatology clinic,” says Brittany Bettendorf, MD, MFA, clinical associate professor of internal medicine-immunology, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

In 2023, an international group of rheumatologists published the first set of classification criteria for CPPD, which describe the disease’s multiple presentations and can help doctors determine how to make a diagnosis in the absence of clear evidence.2 Ann Rosenthal, MD, FACP, associate dean and professor of rheumatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped write those criteria to address what she says is a a “highly underdiagnosed” disease that can be challenging to identify.

Management is further complicated by significant clinical overlap among the different CPPD presentations and the potential for one form to follow another. The disease can also jump around the body. “Some people have it in the same joint, and some people will get it in new joints every time they get a flare, so it’s unpredictable,” says Dr. Rosenthal.

Various terms have been used to describe CPPD and its forms, “which adds to the confusion for clinicians,” says Herbert Baraf, MD, FACP, MACR, clinical professor of medicine, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. CPPD can present as a completely asymptomatic condition, sometimes called lanthanic CPPD. In one study from 1975, nearly three in 10 older patients showed X-ray evidence of chondrocalcinosis or deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in the cartilage in their knees, hips or pelvis.3 Although many of the patients had a history of arthritis, roughly half had few or no symptoms. In such cases, the condition is diagnosed primarily on the basis of radiographs showing the calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposits.