Discussion

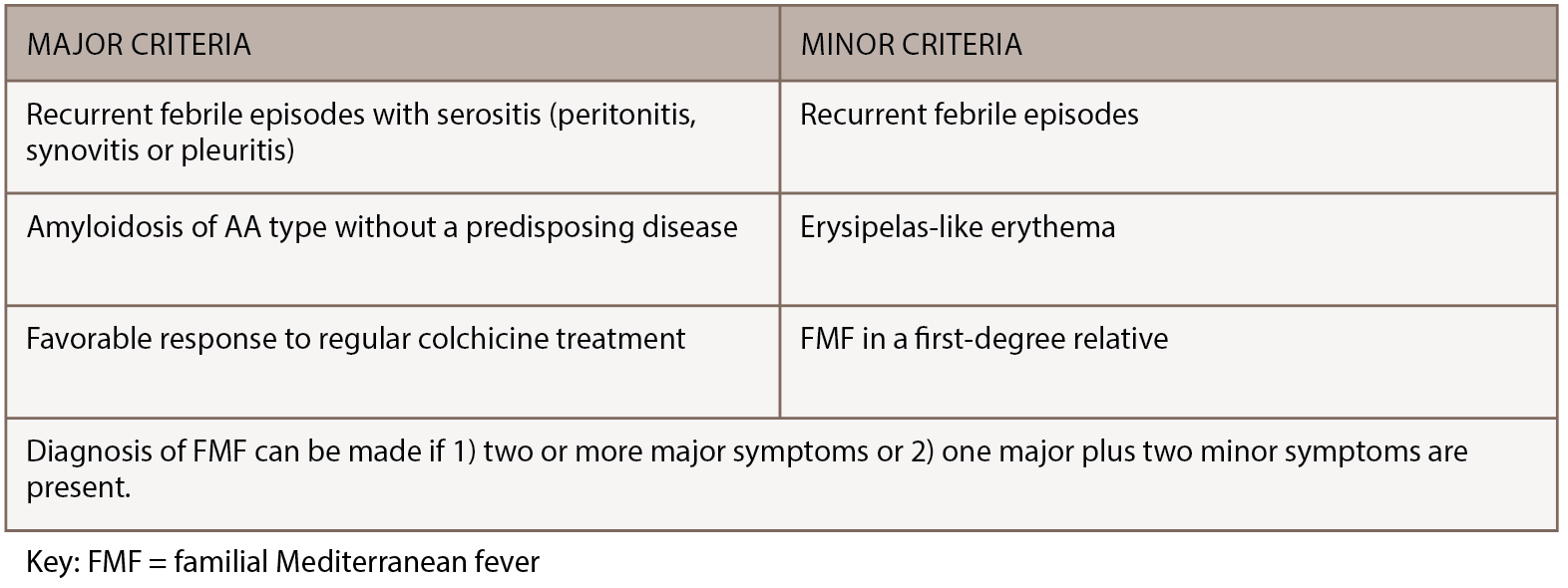

FMF is a rare, inherited disorder characterized by recurrent bouts of inflammation affecting the abdomen, chest or joints. Episodes last 12–72 hours, can vary in severity and are often accompanied by fever, erysipelas-like rash or headache. Although genetic testing for MEFV mutations is preferred when making an FMF diagnosis, the diagnosis remains clinical, because mutations have varying penetrance and homozygosity cannot always be demonstrated.3 FMF diagnosis can be made using the Tel-Hashomer clinical criteria, in which two or more major symptoms or one major plus two minor symptoms are present.4 (Major and minor Tel-Hashomer clinical criteria appear in Table 2) Livneh et al. suggested a version of FMF diagnostic criteria that included descriptions of typical and incomplete symptoms, as noted in Table 3 (opposite).5 As access to genetic testing for FMF expands, identification of biallelic MEFV pathogenic variants can confirm the diagnosis.

But how does the clinician make a diagnosis of FMF when atypical clinical manifestations or, as in this case, musculoskeletal predominant symptoms are the main features? For this patient, after an extensive serologic and radiographic workup for the presence of other systemic autoimmune arthritides was unrevealing, arthrocentesis and, ultimately, MRI of the knee were pursued to determine if an intra-articular etiology, such as pigmented villonodular synovitis, for his recent swelling was present. These studies were also unrevealing. It wasn’t until the patient showed photos of his knees on his smartphone to the rheumatologist that a break in the case occurred. Ultimately, it was a combination of persistence by both the patient and the physician, as well as the ability to evaluate the patient expeditiously, that suggested he might have an autoinflammatory disorder.

Figure 1: The patient provided photos of both knees. Note the swelling in suprapatellar bursa and loss of medial/lateral peripatellar fossa.

How does the clinician proceed with establishing a diagnosis of FMF when only one allelic variant is present? Although FMF is typically described as an autosomal recessive disorder, it is becoming increasingly well known that up to 30% of patients with FMF have only one detected pathogenic MEFV variant despite sequencing of the entire coding region. These patients frequently have a typical clinical history and respond well to colchicine.2

Multiple reasons for this phenomenon exist. First, some routine genetic screening tests might target only the most prevalent mutations, so novel or rare mutations might be missed.2 Indeed, several mutations (i.e., E148Q on exon 2 and M680I, M694I, M694V and V726A on exon 10) may be responsible for up to 80% of FMF cases in classically affected populations.2

Additionally, the second mutation lies in intronic or regulatory regions (perhaps affecting messenger RNA) and thus isn’t screened for unless the entire gene was sequenced. Third, a few disease-associated mutations are gene rearrangements, such as a deletion, and not the typical missense nucleotide changes routinely screened for.2 Fourth, several pedigrees have been described with family members affected in an autosomal dominant pattern.6,7

Finally, the presence of one or several modifying genes may produce a clinical picture similar to FMF through their modulation of the innate immune response.3 Evidence exists suggesting that major histocompatibility complex class I, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA‑A) and class II alleles, exert a differential effect on the clinical picture and response to colchicine in a Japanese population.3 The influence of these alleles may lead to the achievement of an inflammatory dosage threshold necessary for the systemic inflammation and ultimate presentation of FMF.2

In this patient, not all of the typical symptoms of FMF were present, but after several visits and a frustrating, unrevealing workup for a systemic autoimmune or inflammatory arthritis, the patient presented with a picture that clearly documented swelling in his knee. He was evaluated expeditiously and found 48–72 hours later to have had a substantial amount of improvement in his swelling. At this point, an autoinflammatory etiology was entertained.

Testing for FMF yielded heterozygosity for the K695R mutation in pyrin. Although this is a fairly obscure mutation, it is becoming increasingly recognized as associated with a severe clinical phenotype and associated with frequent bouts of arthritis, even when heterozygous.8,9 At a molecular level, although both lysine (K) and arginine (R) are basic amino acids with positively charged side chains, the change would be expected to alter protein function.10