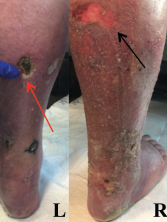

Figure 1: Lower Extremity Ulceration

Varying stages of ulceration are seen on the left (L) and right (R) lower extremities. An eschar formation is on the left (red arrow), and a superficial ulceration is on the right (black arrow).

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that typically affects medium-sized muscular arteries. The clinical subsets of PAN are idiopathic, generalized, secondary hepatitis B virus (HBV) associated and cutaneous PAN. These clinical subsets are important because of their therapeutic implications.

Virtually any organ system can be affected in generalized PAN, but this vasculitis tends to spare the lungs.1 Pleural effusion, transient infiltrates and bronchial artery vasculitis are uncommon manifestations that have been reported in association with PAN.2 These pulmonary manifestations tend to be a reflection of renal or cardiac insufficiency rather than a direct result of the necrotizing vasculitis.

In the case below, we report on the unusual occurrence of shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) and brachial plexopathy in a confirmed case of PAN. This case highlights a broader consideration for the etiology of dyspnea in PAN and adds to the list of immune-mediated diseases associated with SLS and Parsonage-Turner syndrome (PTS).

Case Presentation

A 51-year-old man presented to the hospital with a four-month history of recurrent, bilateral, lower extremity edema and ulcerations that had been treated with intermittent courses of corticosteroids. The ulcers recurred whenever the corticosteroids were tapered. The patient had experienced fever, dyspnea, orchitis, postprandial abdominal pain, uncontrolled hypertension and intermittent right arm pain during the course of his illness. Just prior to hospitalization he had developed dyspnea. His examination was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient’s past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and coronary artery disease. His family history was notable for Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). He had a history of smoking tobacco, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On our initial physical examination, the patient had normal vital signs. Despite his complaints of dyspnea and orthopnea, he had normal pulmonary and cardiac examinations. The muscle strength in his right upper arm was 3/5, and he had pitting edema on his lower extremities.

The examination of the patient’s skin was notable for livedo reticularis and ulceration of the lower extremities, extending from the calves to the heels of his feet (see Figure 1, above). The ulcers were of varying stages, with some being early stage and superficial, and other lesions deep with eschar formation.

Laboratory analysis is listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Laboratory Test Results

| Laboratory | Test Result* | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| White cell count | 11.6 K/uL | 4.8–10.8 K/uL |

| Serum eosinophil % | 0.036 | 0.0–6.1% |

| Serum eosinophil (number) | 0.4 K/uL | 0.0–0.4 K/uL |

| Hemoglobin | 12.4 g/dL | 14–18 g/dL |

| Platelet | 385 K/uL | 140–420 K/uL |

| Serum creatinine | 0.9 mg/dL | 0.6–1.3 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 21 IU/L | 15–41 IU/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 35 IU/L | 12–63 IU/L |

| Creatine phosphokinase (CPK) | 110 IU/L | 25–250 IU/L |

| C-reactive protein | 1.63 mg/dL | 0–0.6 mg/dL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 62 MM/HR | 0–15 MM/HR |

| Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) | 1:640 titer (nucleolar) | <1:80 titer |

| Anti-proteinase 3 (anti-PR3) | <3.5 U/mL | 0.0–3.5 U/mL |

| Anti-myeloperoxidase (anti-MPO) | <9.0 U/mL | 0.0–9.0 U/mL |

| Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) | Negative | Negative |

| Interleukin-6 | 2.4 pg/mL | 0.0–15.5 pg/mL |

| Interleukin-2 | <31.2 pg/mL | 0.0–31.2 pg/mL |

| IgE, Total | 779 IU/mL | 6–495 IU/mL |

| C3 complement | 117.0 mg/dL | 90–180 mg/dL |

| C4 complement | 28.0 mg/dL | 10–40 mg/dL |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Nonreactive | Negative |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| HIV screen (AB/AG combo) | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| B-type natriuretic peptide | 12 pg/mL | 0–100 pg/mL |

| Urine blood | Negative | Negative |

| Urine protein | Negative | Negative |

| *abnormal findings indicated in bold |

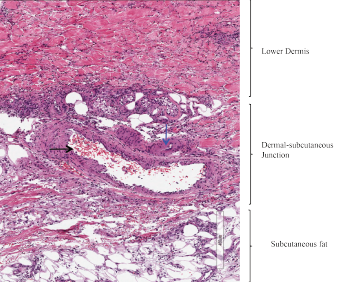

A punch biopsy of an ulcer from the left lower extremity revealed medium-sized blood vessels in the dermis and dermal-subcutaneous junction, with fibrin deposition in walls, neutrophils, and extravasated neutrophils and erythrocytes in the interstitium (see Figure 2). Histologic features of the skin biopsy were consistent with PAN.

Figure 2: Skin Biopsy

Medium-sized blood vessels are seen in the dermis and at the dermal-subcutaneous junction. The black arrow identifies a venule, and the blue arrow points to a fibrin deposition in the vessel wall. Extravasated neutrophils and erythrocytes are seen in the interstitium.

Treatment with corticosteroids was initiated for the management of cutaneous PAN. The patient reported improvement in the pain caused by his skin lesions; however, his dyspnea, orthopnea and right upper extremity pain persisted.

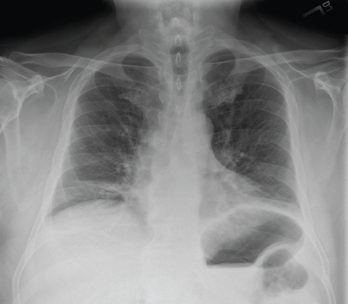

His chest X-ray suggested low lung volumes (see Figure 3), but computed tomography (CT) of the thorax did not demonstrate parenchymal abnormalities, and CT angiography was unremarkable. Pulmonary function testing revealed a decreased forced vital capacity (FVC) of 33%, forced expiratory volume (FEV1) of 32%, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 55%, with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio (97).

An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm with borderline left ventricular hypertrophy by criteria. A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a normal ejection fraction with concentric remodeling, and right heart catheterization showed normal filling pressures.

Due to his persistent right arm pain and weakness, the patient underwent electromyography of the right upper extremity. It was suggestive of an inflammatory plexopathy.

We diagnosed PAN with associated shrinking lung syndrome and brachial plexopathy. Shrinking lung syndrome was diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s persistent dyspnea and orthopnea, restrictive pulmonary function tests (PFTs), low lung volumes and a normal CT of the thorax.

Figure 3: Chest X-ray (Posteroanterior View)

Low lung volumes are appreciated bilaterally, along with subsegmental atelectasis at the right lung base.

The patient was treated with high-dose glucocorticoids, resulting in improvement of his lower extremity ulcers and orchitis. Azathioprine was added as a steroid-sparing agent. Despite improvement in his skin ulcers, he continued to report dyspnea and right arm pain. Azathioprine was changed to methotrexate after he experienced gastrointestinal intolerance. He developed abdominal pain, worsening dyspnea and hyponatremia while on methotrexate, so this medication was discontinued.

More aggressive immunomodulatory therapy with cyclophosphamide was initiated as a result of diaphragmatic weakness and brachial plexopathy attributed to PAN. His clinical course was complicated by hemorrhagic shock, hypoxic respiratory failure and sepsis. Cyclophosphamide was subsequently discontinued. After his recovery and an infection-free interval of a month, he was treated with rituximab for persistent dyspnea. He eventually developed multi-organ failure, which ultimately led to his death.

Discussion

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that typically affects medium- and small-sized muscular arteries but spares small vessels, such as arterioles, capillaries and venules.1 It is a rare disease that has become even less common with widespread immunization against HBV and better diagnostic criteria for other systemic, necrotizing vasculitides.3

PAN affects men more often than women, with an average age of onset between 40 and 60 years. Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, myalgias and weight loss, along with peripheral neuropathy, are the most common presenting symptoms associated with PAN.1,4 Nearly 60% of patients with generalized PAN develop cutaneous manifestations. About 20% of patients develop orchitis; less commonly, patients may present with gastrointestinal symptoms, including the severe manifestation of an acute abdomen.1,5

Mononeuritis multiplex is the most common neurologic manifestation in PAN and may be present in up to 75% of patients.1 Rarely, brachial or lumbosacral plexopathies, as seen in our patient, have been associated with PAN. Other rare neurologic manifestations include radicular syndromes and a clinical presentation similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome.4

Dyspnea

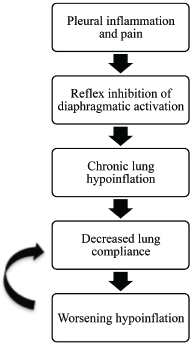

Figure 4: Positive Feedback Loop

A positive feedback loop is a theory proposed to explain the pathophysiology of shrinking lung syndrome.

PAN can affect virtually any organ, but tends to spare the lungs.1 However, rheumatologists should recognize dyspnea and possible pulmonary pathology complicating this medium-vessel vasculitis. We describe shrinking lung syndrome and PTS as two pulmonary manifestations potentially associated with PAN.

Shrinking lung syndrome is a rare cause of dyspnea characterized by a progressive decline in lung volumes without evidence of pleural or interstitial lung disease. In SLS, chest radiography reveals decreased lung volumes with an elevated hemidiaphragm, pulmonary function testing is consistent with a restrictive pattern, and the workup for dyspnea excludes major parenchymal or pleural disease on CT imaging.6 All of the above characteristics were present in our patient’s case, leading to a diagnosis of SLS as the etiology of his dyspnea.

SLS has been described in the literature mainly in the context of SLE.6 The prevalence of SLS in patients with SLE is <1%, where it tends to be a late pulmonary manifestation.7 Duron et al. evaluated 15 cases of SLS in SLE and found all cases occurred in women with a median age of 27 years at onset.8 Table 2 shares a small sampling of case reports of SLS cases in a variety of autoimmune diseases.7,9,10 A 2017 case series and literature review by Smyth et al. found 89 cases of SLS reported in the literature.11

Table 2: Shrinking Lung Syndrome Case Reports

| Autoimmune Disease | Age/Sex of Patient | Presenting Symptoms | Diagnostic Criteria Met |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 18-year-old male | Dyspnea and pleuritic | Chest X-ray with elevation of right hemidiaphragm; pulmonary function tests (PFTs) with severe restrictive pattern; computed tomography (CT) thorax with normal lung parenchyma |

| Systemic Sclerosis | 48-year-old female | Chest pain | Chest X-ray with small lung fields and raised right hemidiaphragm; PFTs with restrictive pattern; CT thorax with normal lung parenchyma |

| Sjögren’s Syndrome | 56-year-old female | Dyspnea on exertion | Chest X-ray clear with small lung fields, elevated right hemidiaphragm; PFTs with restrictive pattern; CT thorax with normal lung parenchyma |

PTS is an idiopathic brachialathy with an abrupt onset of symptoms. Multiple conditions have been associated with the development of PTS, including stressful exercise, infection, immunizations, surgery, pregnancy and rheumatic diseases, such as SLE, PAN, giant cell arteritis and connective-tissue disease (see Table 3).12,13

Table 3: Parsonage-Turner Syndrome Case Reports

| Autoimmune Disease | Age/Sex of Patient | Presenting Symptoms | Diagnostic Criteria Met |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAN | 78-year-old male | Bilateral arm weakness, shoulder pain | Normal electromyography, brachial plexopathy on exam |

| Temporal Arteritis | 75-year-old male | Progressive loss of strength of right upper extremity, unable to abduct or externally rotate arm, unable to flex or supinate forearm | Electromyography with C5 radiculopathy |

Nerve involvement in PTS tends to be unilateral, but can be bilateral and may involve nerves outside the brachial plexus, such as the phrenic nerve. When the phrenic nerve is involved, patients may experience dyspnea and have evidence of diaphragmatic elevation on chest X-ray.14 Our patient’s low lung volumes could, therefore, have been due to SLS or PTS resulting in phrenic nerve dysfunction.

Pathogenesis of PAN

The pathogenesis of PAN is not well understood, but the disease can be either idiopathic or triggered. Triggered causes of PAN include infections with parvovirus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses, as well as hairy-cell leukemia.1 PAN was initially thought to be an immune complex-mediated disease due to the injury pattern of blood vessels, but complement consumption is rare.3

PAN differs from other systemic necrotizing vasculitides in that anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are typically absent and histopathologic features of granulomatous inflammation exclude a diagnosis of PAN.1,4 The histopathologic finding characteristic for PAN is focal, segmental, pan-mural necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized or small arteries, predominantly at branch points and bifurcations of these vessels.5 Early, active lesions biopsied from symptomatic sites may reveal fibrinoid necrosis, as was noted in our patient’s skin biopsy.1 However, because PAN generally presents with successive flares, multiple histologic stages may present simultaneously.4

The pathophysiology of PTS and SLS is poorly understood. Shrinking lung syndrome presents with pleuritic chest pain in nearly 75% of cases. The pleuritic pain and inflammation are thought to trigger reflex inhibition of diaphragmatic activation. This inhibition leads to chronic lung hypoinflation, which ultimately leads to decreased lung compliance.

It is not fully understood why lung compliance worsens, but tissue remodeling and changes in surfactant are suspected contributing factors. Decreased lung compliance propagates lung hypoinflation, which initiates a positive feedback loop (see Figure 4, above). The etiology of SLS is likely multi-factorial, and the aforementioned theory accounts for only a portion of SLS cases.

Approximately 25% of patients with SLS do not present with pleuritic chest pain (as was true with our patient).15 Other proposed theories for the pathophysiology of SLS include pleural adhesions leading to diaphragmatic dysfunction, surfactant deficiency causing increased surface tension and subsequent micro-atelectasis, and the development of an inspiratory and expiratory myopathy or phrenic neuropathy.11 Our patient may have had some level of phrenic neuropathy caused by PAN.

Nerve ischemia from either an inflammatory or mechanical etiology is thought to result in the symptoms of PTS. In PTS associated with vasculitic conditions, a vascular etiology contributing to the development of PTS is postulated.14 There is limited understanding about why the brachial plexus is involved.

Treatment of Idiopathic PAN

Treatment of idiopathic PAN usually begins with corticosteroid therapy at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day.1 The Five-Factor Score (FFS) is a prognostic index used to determine if immunosuppressive therapy, in addition to corticosteroid therapy, is warranted. Each of the following manifestations receives one point on the FFS: renal insufficiency (serum creatinine level >1.7 mg/dL), gastrointestinal involvement, cardiac involvement and age >65 years. If a patient has a score of 1 or higher, the recommended treatment is a combination of cyclophosphamide and prednisone to achieve remission. Patients may be switched to a steroid-sparing agent, such as azathioprine or methotrexate, once remission is achieved.1

Relapses occur in up to 20% of idiopathic PAN cases.5 The five-year mortality rate is 12% for PAN patients with an FFS of 0, 26% for patients with an FFS of 1, and 46% for patients with an FFS ≥2.5 In our case, the patient’s abdominal pain was not attributed to his diagnosis of PAN because it was self-limited (i.e., resolving before his initial hospital admission) and his CT angiography was unremarkable. His FFS was therefore 0, which led to the initial decision to treat his cutaneous lesions with prednisone alone.

Treatment of SLS targets the underlying disease process and involves immunosuppressive therapy.6 In contrast, the management of symptoms associated with PTS primarily involves physical therapy, and recovery may take several years.14 Our patient predominantly presented with cutaneous manifestations of PAN and did not have any of the poor prognostic factors. However, his recalcitrant symptoms of dyspnea and right arm pain attributed to SLS and/or PTS illustrate that some vasculitic manifestations may be refractory to corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusion

We describe a rare case of idiopathic polyarteritis nodosa with primarily cutaneous disease. Cutaneous PAN is associated with a lower mortality, although lesions may be refractory to treatment and tend to be recurrent.1

In our patient, with predominantly cutaneous manifestations of PAN and a Five-Factor Score of 0, the historical factors, along with the diagnosis of shrinking lung syndrome and PTS, led to the combination of corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy.

In spite of our patient’s dismal outcome, we emphasize that early recognition of shrinking lung syndrome and PTS as possible complications in PAN may warrant early, aggressive therapy to improve outcomes.

Hannah Krebsbach, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. She completed her internal medicine residency at Tulane University, New Orleans, and medical school at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis.

Hannah Krebsbach, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. She completed her internal medicine residency at Tulane University, New Orleans, and medical school at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis.

Ileannette M. Robledo Vega, MD, is a staff rheumatologist at Crescent City Physicians Inc., New Orleans.

Ileannette M. Robledo Vega, MD, is a staff rheumatologist at Crescent City Physicians Inc., New Orleans.

Nirupa Patel, MD, is an associate professor of clinical medicine—gratis in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

Nirupa Patel, MD, is an associate professor of clinical medicine—gratis in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

Nkechinyere Emejuaiwe, MD, MPH, is a staff rheumatologist at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center, with an adjunct faculty appointment at the University of Cincinnati.

Nkechinyere Emejuaiwe, MD, MPH, is a staff rheumatologist at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center, with an adjunct faculty appointment at the University of Cincinnati.

New PAN Guideline

The ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation recently published a new PAN guideline. For details, click here.

References

- Forbess L, Bannykh S. Polyarteritis nodosa. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(1):33–46, vii.

- Adams TN, Zhang D, Batra K, Fitzgerald J. Pulmonary manifestations of large, medium, and variable vessel vasculitis. Respir Med. 2018 Dec;145:182–191.

- Hernández-Rodríguez J, Alba MA, Prieto-González S, Cid MC. Diagnosis and classification of polyarteritis nodosa. J Autoimmun. Feb-Mar 2014;48–49:84–89.

- de Boysson H, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa neurologic manifestations. Neurol Clin. 2019 May;37(2):345–357.

- De Virgilio A, Greco A, Magliulo G, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa: A contemporary overview. Autoimmun Rev. 2016 Jun;15(6):564–70.

- Karim MY, Miranda LC, Tench CM, et al. Presentation and prognosis of the shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Apr;31(5):289–298.

- Pillai S, Mehta J, Levin T, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome presenting as an initial pulmonary manifestation of SLE. Lupus. 2014 Oct;23(11):1201–1203.

- Duron L, Cohen-Aubart F, Diot E, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: A multicenter collaborative study of 15 new cases and a review of the 155 cases in the literature focusing on treatment response and long-term outcomes. Autoimmun Rev. 2016 Oct;15(10):994–1000.

- Scirè CA, Caporali R, Zanierato M, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Oct;48(10):2999–3000.

- Tavoni A, Vitali C, Cirigliano G, et al. Shrinking lung in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Oct;42(10):2249–2254.

- Smyth H, Flood R, Kane D, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series and literature review. QJM. 2018 Dec 1;111(12):839–843.

- Allan SG, Towla HM, Smith CC, et al. Painful brachial plexopathy: An unusual presentation of polyarteritis nodosa. Postgrad Med J. 1982 May;58(679):311–313.

- Cordero Sánchez M, Calvo Arenillas JI, Gutierrez DA, et al. Cervical radiculopathy: A rare symptom of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1983 Feb;26(2):207–209.

- Feinberg JH, Radecki J. Parsonage-turner syndrome. HSS J. 2010 Sep;6(2):199–205.

- Borrell H, Narváez J, Alegre JJ, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Aug;95(33):e4626.