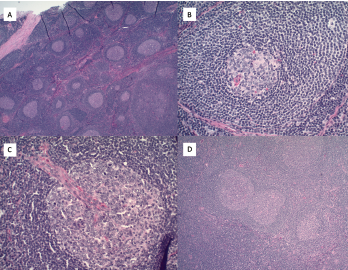

Figure 2. A) Hematoxylin and eosin stains at 2x magnification show follicular hyperplasia with hyperplastic germinal center and some regressed germinal centers; B) atretic follicle surrounded by expanded onion-skin mantle zone at 20x magnification; C) increased vascularity including perpendicularly penetrating vessels into follicles resulting in lollipop forms at 20x magnification; and D) twinning of germinal centers at 4x magnification.

Originally described by Benjamin Castleman, MD, in 1954, Castleman disease is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder that has clinical overlap with rheumatic diseases.3 With a yearly incidence of approximately 5,000 patients in the U.S., it remains challenging to diagnose and treat.4

Although manifestations of Castleman disease vary, lymphadenopathy, constitutional symptoms and anemia without obvious cause should prompt diagnostic consideration. Abdominal pain is also relatively common. Proteinuria (potentially due to renal podocyte damage) and amyloidosis are known long-term complications.5

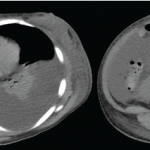

Castleman disease is clinically divided into unicentric disease (UCD), involving a single lymph node station, as in this case, or multicentric disease (MCD), involving multiple lymph nodes.6-8 A possible third entity, oligocentric or regional CD, involves lymph nodes in two or three adjacent lymph node stations and is not yet well understood. The involved lymph node or nodes may be found anywhere in the body; common locations include the abdomen, neck and mediastinum.9

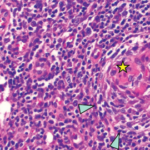

Pathologic features include regressed germinal centers, follicular dendritic cell prominence, vascularity, hyperplastic germinal centers and plasmacytosis.6 Fine needle aspiration is usually insufficient to reveal diagnostic lymph node structure. The mechanism of Castleman disease remains ill-defined, but B cell and blood vessel proliferation mediated by interleukin 6 (IL-6) is thought to play a role.10

Up to 40% of Castleman patients have anti-nuclear antibodies, underscoring the need for a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis.11As symptoms and pathologic features of Castleman disease occur in other illnesses, including those of autoimmune, infectious and malignant origin, a broad evaluation is essential.

A differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy with features of Castleman disease should include the following etiologies:

- Infectious: acute Epstein-Barr virus (EBV); HIV; tuberculosis;

- Autoimmune or inflammatory: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); rheumatoid arthritis-related lymphoproliferative disorders; IgG4-related disease; and

- Genetic or acquired lymphoproliferative diseases: lymphoma; autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS).6

Castleman Disease Subtypes

Further differentiating between UCD and MCD is important because their prognoses and treatment are distinct. UCD, which tends to affect younger people than MCD, has an excellent prognosis if the mass is fully excised. Excisional surgery is diagnostic and typically curative, with only rare recurrence in the same location or in a different area.4,9 Immunosuppressive treatment may be required in the case of unresectable UCD that is causing symptoms.

In contrast, the prognosis in MCD is mixed.12 MCD can be subdivided into human herpesvirus 8- (HHV8-) associated MCD; POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, skin changes) syndrome-associated; and idiopathic (iMCD) subsets.6 Patients with iMCD may have thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis of bone marrow and organomegaly (TAFRO). The TAFRO entity carries a poorer prognosis.9

Up to 40% of patients [with Castleman disease] have anti-nuclear antibodies, underscoring the need for a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosing this disease.

For iMCD, anti-IL-6 therapy, such as siltuximab, is the first-line treatment, and rituximab is an alternative. Prednisone may be required as an initial therapy and to control disease flares.7

Treatment is best performed in collaboration with a hematologist who has experience treating Castleman disease and screening for potential complications.

Minimizing Diagnostic Delays

Our patient was clinically symptomatic for nine years prior to her diagnosis. Several factors likely contributed to this delay. These included her busy schedule and a reluctance to pursue an aggressive evaluation in the setting of years of perceived unsuccessful visits with multiple doctors. She also appeared healthy, and her atypical clinical presentation did not suggest a clear etiology or even a relevant clinical specialty.

Correctly diagnosing such a patient is challenging, requiring continued longitudinal visits, open communication and a willingness by both the patient and rheumatologist to pursue further testing in the face of ongoing diagnostic uncertainty.

Lisa L. Korn, MD, PhD, is a rheumatology fellow in the departments of medicine and immunobiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Lisa L. Korn, MD, PhD, is a rheumatology fellow in the departments of medicine and immunobiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Mina L. Xu, MD, is an assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and the director of hematopathology at Yale University.

Mina L. Xu, MD, is an assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and the director of hematopathology at Yale University.

Cristina Brunet, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Yale University.

Cristina Brunet, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Yale University.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient for allowing us to publish her case.

Disclosure

Lisa L. Korn, MD, PhD, was supported by the Training Program in Investigative Rheumatology (5T32AR07107).

References

- Schönau V, Vogel K, Englbrecht M, et al. The value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in identifying the cause of fever of unknown origin (FUO) and inflammation of unknown origin (IUO): data from a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jan;77(1):70–77.

- Banchereau R, Cepika A-M, Banchereau J, Pascual V. Understanding human autoimmunity and autoinflammation through transcriptomics. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35(1):337–370.

- Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital weekly clinicopathological exercises: Case 40011. N Engl J Med. 1954 Jan 7;250(1):26–30.

- Simpson D. Epidemiology of Castleman Disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018 Feb;32(1):1–10.

- El Karoui K, Vuiblet V, Dion D, et al. Renal involvement in Castleman disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011 Feb;26(2):599–609.

- Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, et al. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8–negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2017 Mar 23;129(12):1646–1657.

- van Rhee F, Voorhees P, Dispenzieri A, et al. International, evidence-based consensus treatment guidelines for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018 Nov 15;132(20):2115–2124.

- van Rhee F, Oksenhendler E, Srkalovic G, et al. International evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. 2020 Dec 8;4(23):6039–6050.

- Yu L, Tu M, Cortes J, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of HIV- and HHV-8–negative Castleman disease. Blood. 2017 Mar 23;129(12):1658–1668.

- Fajgenbaum DC, Shilling D. Castleman disease pathogenesis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):11–21.

- Liu AY, Nabel CS, Finkelman BS, et al. Idiopathic multicentric Castleman’s disease: A systematic literature review. Lancet Haematol. 2016 Apr;3(4):e163–75.

- Oksenhendler E, Boutboul D, Fajgenbaum D, et al. The full spectrum of Castleman disease: 273 patients studied over 20 years. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(2):206–216.