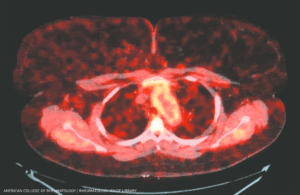

Takayasu arteritis: Aortic root enhancement on a PET-CT scan. A 30-year-old woman with long-standing Takayasu arteritis on infliximab and methotrexate developed chest pain and left arm claudication. PET scan showed 18-fluorodeoxyglucose avidity of the wall of the aortic root and arch indicative of active aortitis. (Click to enlarge.)

The rare systemic inflammatory disease known as Takayasu arteritis primarily targets the aorta and its major branches, such as the carotid arteries that direct oxygenated blood to the brain. Chronic inflammation of the arteries can yield complications, such as aneurysms and stenosis, or a narrowing and blocking of blood vessels that can prevent parts of the body from receiving enough blood and oxygen. This ischemia can lead to tissue damage.

Researchers remain in the dark about the underlying cause of Takayasu arteritis, adding to the challenges of identifying and managing the disease. “We still don’t understand, for example, how much genetics, relative to non-genetic factors, contribute to the disease etiology,” says Amr H. Sawalha, MD, chair of the Department of Pediatric Rheumatology and director of the Comprehensive Lupus Center of Excellence at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Over the past decade, however, multiple large-scale genetic studies have revealed some important details about genetic susceptibility to Takayasu arteritis. In a recent review and analysis in ACR Open Rheumatology, Dr. Sawalha and post-doctoral fellow Desiré Casares-Marfil, PhD, have built upon that evidence with genetic associations that could help uncover pivotal molecular pathways, potential therapeutic targets and promising drug candidates.1 From the data, they devised a cumulative genetic risk score that confirmed differences in risk among people with different genetic ancestries, and developed a practical guide for communicating the risk to patients and their families.

New Susceptibility Clues

Takayasu arteritis is much less common than another type of large vessel vasculitis known as giant cell arteritis. The Takayasu type also tends to strike younger patients—primarily women, with a typical onset between the ages of 20 and 40. It is most prevalent in Asia, with about 40 cases per million people, whereas its prevalence in the U.S. is roughly fivefold lower. “It is a challenge because when it starts, it tends to be insidious in onset,” Dr. Sawalha says. “Basically, patients might not have very specific symptoms when they first present.” Some clinical clues can point toward Takayasu arteritis, however, like ischemic changes and symptoms related to blood vessel inflammation. Immunosuppressive medications are the usual first line of treatment.