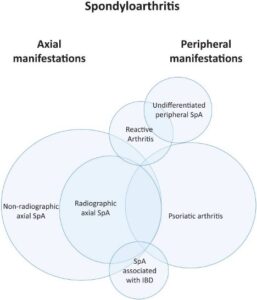

The spondyloarthropathies encompass a group of related rheumatic diseases characterized by arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis with variable degrees of peripheral and axial involvement. These diseases include radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, undifferentiated peripheral spondyloarthritis, inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis (i.e., enteropathic arthritis) and reactive arthritis (see Figure 1).13

Alexis Ogdie, MD, MSCE, associate professor of medicine and associate professor of epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, as well as an expert in spondyloarthritis, estimates she has seen only a few cases of reactive arthritis among a larger cohort of patients with spondyloarthritis, which is reflected in the rarity of reactive arthritis represented in previously published spondyloarthritis registries.14

With no validated diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of reactive arthritis is based on clinical factors. The most widely used criteria for reactive arthritis were proposed by the ACR in 1999 and Braun et al. in 2000.7 The more recent Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) classification criteria for spondyloarthritis do not formally include reactive arthritis; however, the classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis include preceding infection.15

Clinical Presentation

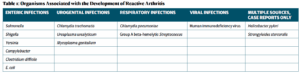

Reactive arthritis usually presents as an acute, asymmetric oligoarthritis one to two weeks after onset of a gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, but can occur up to four weeks after infection with Chlamydia trachomatis.5 Common precipitating organisms include gut bacteria, such as Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter, and urogenital tract organisms, such as Chlamydia, Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma. Additional culprit organisms are highlighted in Table 1.5

At disease onset, analysis of synovial fluid can help exclude septic arthritis. Synovial fluid will be inflammatory, with 2,000–64,000 white blood cells, but synovial cultures will be negative.5 Evidence of preceding infection should be sought, although no definite recommended laboratory testing has been established, and often the precipitating infection may go undetected due to lack of symptoms. In fact, a prior infection is identified in only 60% of patients clinically diagnosed with reactive arthritis.16

John Miller, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center, Baltimore, says “the clinical presentation (e.g., diarrhea, hematochezia, dysuria) will often guide the evaluation for infectious etiology. This usually includes stool or urine cultures and nucleic acid testing; however, many other pathogens have been implicated in reactive arthritis (e.g., Giardia, Strongyloides, Clostridium difficile), so additional testing may be necessary, depending on the initial symptoms.”