To simplify this categorization, we can identify two forms of WG: 1) a complete form (systemic or generalized WG) that is characterized by both granulomatous and vasculitic manifestations and presents ultimately as the organ- and life-threatening pulmonary–renal vasculitis syndrome; and 2) an incomplete form of WG that is categorized as localized WG. In this form, the disease occurs solely as granulomatous inflammation that is restricted to the upper and/or lower respiratory tract without any other systemic involvement or constitutional symptoms. These two forms differ from previous approaches to clinical classification—which, in turn, has an impact on ideas related to disease pathogenesis and specifically related to the interplay of granulomas inflammation and frank vasculitis.

The previous concept for understanding WG, both clinically and mechanistically, related to chronology. In this scheme, localized WG could appear initially as a short-term and “mild” disease stage (localized WG) before patients increased their level of disease severity with ensuing vasculitic symptoms to develop complete WG. Yet, rarely, localized WG may persist for decades as primarily a chronic granulomatous inflammatory process restricted to the respiratory tract. This aspect of disease has been described only recently in a systematic approach by two European cohort studies.9,10 Furthermore, this necrotizing granulomatous inflammation can cause more severe local and long-term organ damage than previously thought.11

Clinical Spectrum of WG

In the past, the major fatal outcome of untreated and generalized WG was associated with manifestations of vasculitis such as alveolar hemorrhage (due to capillaritis of the lungs) or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (due to pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis), leading to vital organ failure within days or weeks. This fatal outcome of full-blown (generalized or severe) WG is less frequent today due to earlier diagnosis and improved treatment strategies. However, the mortality rate is still high (around 11% [range, 2.2%–25%] depending on disease stage and intensity of treatment), especially within the first year of diagnosis.12

Because of improved diagnostic techniques, the growing awareness of orphan diseases in the medical community and the major improvement of therapeutic strategies, WG is now recognized in a wider clinical spectrum that encompasses not only systemic vasculitis manifestations but also chronic granulomatous manifestations of the respiratory tract. Indeed, in the everyday care situation of patients with WG, the majority of patients with “grumbling” and/or relapsing disease suffer from the ongoing granulomatous process rather than from vasculitis.

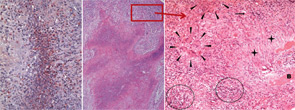

Regarding localized disease manifestation, mucosal ulceration leading to bloody rhinitis is seen by nasal endoscopy during the beginning of the disease; later, septum infiltration and perforation may occur as well as the destruction of the conchae. Granulomatous masses may be detected by MRI imaging in the sinuses and can be accompanied by bone destruction of the adjacent sinus, ethmoidal cysts, and orbita, leading to proptosis and compression of the optic nerve.13 In addition, per vias naturales the masses can obstruct the lacrimal duct or the subglottic region and, less frequently, bronchi, which may cause subsequent poststenotic pneumonia. Via the ethmoidal cysts, the process rarely invades the intracranial space and brain. In the lung, the masses usually appear as round nodules with a tendency to cavitate (see Figure 1, above).

Damage Induced by Granulomatous Inflammation

Although advances in the treatment of WG have resulted in a dramatic reduction in disease-related mortality, patients still experience relapses due to the vasculitis and the granulomatous process and side effects from treatment toxicity.11 Using damage scores to assess the total burden of damage experienced by the patient, it can be demonstrated that, besides the damage associated with malignancy, tissue ischemia, and organ failure, items of damage obviously associated with the granulomatous process were frequently scored and rated as medium to severe damage items.11 Examples of damage related to granulomas include proptosis, pseudotumor, nasal bridge collapse, subglottic/ large airway obstruction, orbital wall destruction, diplopia, and optic nerve atrophy. These findings show that the so-called granuloma include space-occupying lesions and tissue-destructive events.

right panel, Rheumatology. 2008;47:1111-1113.

Reprinted with permission.

Localized Granulomatosis as a Persistent Variant of WG

Localized WG may occur not only as a short-term disease stage before generalized disease develops. Recently, this form of disease also has been identified by two European centers as a persistent variant.9,10 In our study, persistent localized WG was observed in 5% of patients in a cohort of 1,024 patients with biopsy-compatible WG followed from 1989 to 2009.9 Only around 50% of the patients were ANCA positive. Localized disease manifestations were characterized by destructive and space-occupying lesions and associated with a high rate of organ damage. Furthermore, nearly all patients with granulomatous involvement (89% over the whole course of follow-up) required medium or highly potent immunosuppression such as methotrexate or cyclophosphamide for remission induction. Cotrimoxazole, which was used in half of the patients as initial treatment, was shown to be insufficient to control disease activity in 72%. In spite of close follow-up and step-up of immunosuppression in cases of persistent or refractory disease activity, 66% of patients acquired at least some kind of organ damage (i.e., saddle nose deformity, septal perforation, bony destruction of sinus and orbital walls).