Insights into the pathophysiology of Behçet’s disease & potential treatments

Insights into the pathophysiology of Behçet’s disease & potential treatments

BARCELONA—Few conditions have as fascinating a global distribution as Behçet’s disease, which owes its distribution to the spread of genetic variants along the ancient trade route known as the Silk Road. The prevalence of the disease is currently highest in such countries as Turkey and Iran.1 Despite this geographic idiosyncrasy, cases of Behçet’s disease can be seen across the globe, and it’s important for all rheumatologists to understand the details of its diagnosis and treatment.

At EULAR 2025, during the plenary session, Behçet’s Disease: What Is New, Matteo Piga, MD, associate professor of rheumatology, the Department of Medical Science and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Italy, highlighted significant developments in the research literature from the past year.

Pathophysiology

Dr. Piga began by discussing new findings about the pathophysiology of Behçet’s disease, which can present with a variety of mucocutaneous, articular, ocular, vascular, neurological and gastrointestinal manifestations. As far back as the 1970s, researchers identified the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region as the first genetic region with susceptibility for Behçet’s disease, specifically noting an association between HLA-B51 and the disorder. However, half a century after this discovery, the genetic architecture of the disease is still being explored.2

Dr. Piga noted that Behçet’s disease is a condition with both autoimmune and autoinflammatory features driven by neutrophil hyperactivity, T cell skewing and cytokine imbalance, infectious triggers and molecular mimicry, and endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis.3 Genome-wide association studies have identified at least 21 susceptibility loci—many of which influence immune pathways—that play a role in cytokine signaling, antigen processing and presentation, and innate immunity.2

Behçet’s Uveitis

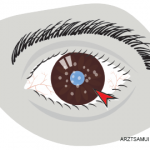

Dr. Piga discussed a fascinating study that sought to evaluate the mechanisms that underlie the increased incidence, severity and poor prognosis of autoinflammatory Behçet’s uveitis in male patients. In this study, the researchers applied single-cell RNA sequencing to circulating neutrophils in the blood of patients with Behçet’s disease-associated uveitis. Proteomic analysis identified upregulation of pathways related to neutrophil extracellular trap formation and downregulation of nucleotide metabolism and apoptosis. Such upregulation was seen more in men than women in the study.

These findings suggest that sex-specific differences in neutrophil function contribute to the immunopathogenesis and clinical heterogeneity of Behçet’s uveitis, with men displaying a more proinflammatory neutrophil phenotype than women. This finding may explain the male-bias in disease severity.4

Advancements in Treatment

Dr. Piga next cited what he indicated was the most important clinical trial in Behçet’s disease of the past year. In a phase 2, multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial from Saadoun et al., 52 patients with severe Behçet’s disease (i.e., defined by major vascular or central nervous system involvement) were randomized to receive either 5 mg/kg of intravenous infliximab at weeks 0, 2, 6, 12 and 18 or 0.7 g/m2 or intravenous cyclophosphamide at weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20, with a maximum dose of 1.2 g/infusion. All patients also received the same background glucocorticoid regimen. The study’s primary outcome was complete response—defined as clinical, biological and radiological remission while on prednisone ≤0.1 mg/kg/day—at week 22.