To date, more than a thousand different species (and many more strains) can be classified into a dozen divisions. Interestingly, only two bacterial divisions (Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes) dominate the gut microbiome. This raw catalog of animalcules is, nonetheless, insufficient. In order to study associations with health and disease, a critical question needed to be addressed: Is there a core microbiome? Do adult human beings share a set of bacteria that could be considered a “normal” reference? The answer appears remarkable. Humans can be clustered into three groups (or enterotypes) according to their microbiome signature.13 In healthy individuals from industrialized nations, these enterotypes are independent of any (studied) host factors. The basis for this evolutionary pressure remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the symbiotic coexistence between microbiota and the host, along with the factors involved in these cross-communications, are becoming better understood. The central question remains: How are we simultaneously tolerating such an antigenic burden of necessary bacteria while fighting undesired ones?

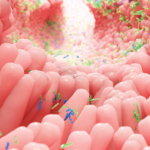

Recent data support the notion that, in health, the gut microbiota signals through the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue and shapes immune responses to promote a homeostatic state. Somehow along the evolutionary process, mammals have learned to utilize these pathways to coexist with this huge antigenic load. A physicochemical and immune barrier also separates the two worlds. A thick mucus layer, antimicrobial proteins and secretory immunoglobulin-A, serves as levees in the biological dike to prevent a flood of undesired flora into this system. A tightly adherent epithelial cell column forms a broader dam to further contain bacterial invasion. If still insufficient, the intestinal lamina propria contains the highest concentration of immune cells in mammals. Bacterial proteins and surface molecules such as lipopolysaccharides and other microbe-associated molecular pattern factors interact with toll-like receptors (TLRs) and related pattern recognition receptors in the host immune cells. Dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells continuously survey the lumen to process, and phagocyte antigens and mount an innate response.

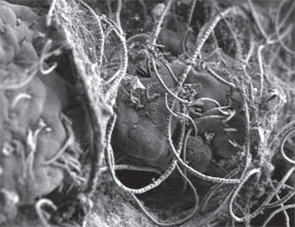

The ultimate balancing act between the host and the microbiome comes from CD4+ T-cells inhabiting the lamina propria. A necessary state of gut mucosal inflammation is driven by T-helper effector cells such as Th1, Th2, and Th17 and their respective signature cytokines, interferon gamma, and interleukins (IL-) 4/13 and 17/22). A tolerogenic subset of T cells, the regulatory T cells (Tregs), actively suppresses and neutralizes potential uncontrolled reactions through IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta. Most recently, it has become clear that a crucial aspect of equilibrium maintenance is directly related to the way the adaptive immune system reacts. Seminal work by Ivanov et al and Round and Mazmanian has recently changed the way we think about the innate and adaptive immunity dichotomy.14,15 Single intestinal commensal bacteria are directly capable of activating CD4+ T-cells and tilting the balance towards pro- or antiinflammatory responses. Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), for example, are sufficient to activate Th17 cells, while a specific polysaccharide of Bacteroides fragilis can promote tolerogenic effects via Treg stimulation (see Figure 3).

The Enemy Within?

When the relative phylogenetic composition of the microbiome is altered, a state of dysbiosis can ensue, and the local immune system can shift towards a proinflammatory milieu (see Figure 4). If this reaction is contained and self-regulated, the outcome is typically helpful, and undesirable pathogens can be cleared. When this state of dysbiosis perpetuates, local inflammation results (as in the case of inflammatory bowel disease) and eventually, deleterious systemic effects arise in a predisposed host. Important elements of this model have received support from both classic and recent compelling studies in animal models, particularly those involving germ-free conditions (animals raised in sterile environments and subsequently challenged with different gut bacteria or their antigens). Notable examples of these studies include Kohashi et al and Bjork et al in adjuvant arthritis, work by Taurog et al in HLA-B27 transgenic rats, and reports by van den Broek et al in streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis rats.16-19