We do this because we have to. We know that some data are better than no data, so we design clinical trials based on the possible, and we hope that lumping disparate patients together will not muddy the message of the clinical study too much.

This practical approach likely leaves us with lumps that are too big. Using the old criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus, for example, a patient would have to meet four of 11 criteria to be classified as having lupus. You may recall from your high school math class that the notation for the number of combinations that may satisfy that straightforward rule is 11!-7!; this translates into almost 40 million different combinations of signs and lab parameters that could be used as proof of a patient’s worthiness to enroll in a clinical trial of lupus. It is difficult to imagine that a single drug would work for all of these clinical presentations, even if they all carry the same name.

A Better Splitter

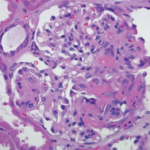

The common pathway is the Achilles heel of clinical classification criteria. For every combination of signs and symptoms that is thought to be pathognomonic for a given rheumatic disease, exceptions to the rule exist. These exceptional patients, with their alternate pathogenesis and alternate mechanisms, likely require alternate treatment approaches, as well. Including these patients in our clinical trials, especially in studies of rare diseases, may introduce just enough variation to nudge the P value for the primary endpoint above 0.05.

It is possible that we have simply reached the limits of clinical classification. It may be asking too much from the poor clinician to differentiate patients whose arthritis is mediated by Th17 from patients whose inflammation is predominately a product of defective Treg cells.

Part of the problem may be that, as clinicians, we may not be as smart as we think we are. Clinical classification may be subject to subconscious, cognitive biases, which we think of as clinical intuition, but may actually be clinical mistakes.

This is not a new concept. In 2011, for example, the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology proposed leaving behind phenotypes in favor of endotypes, which would group patients according to the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism.6

Advances in therapeutics from this point forward may depend on lumping patients together based on mechanism rather than clinical features. In his discussion of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Peter Nigrovic, MD, proposes two ways forward:

- Genetics: Dr. Nigrovic writes, “If genetics reflects mechanism, then shared genetics is strong prima facie evidence of a common pathophysiology.” Further, it seems logical to assume that patients who share a similar pathophysiology are more likely to respond to the same drug than a patient who reached the same phenotype by another route.

- Big Data: Computers are not subject to cognitive biases, and machine learning may identify clinical insights to which we are blinded. Physicians generally think of evaluating patients clinically to identify a phenotype. With machine learning, the analysis can start with the outcome of interest and then work backward to find the clinical and serologic clues that predict that outcome.

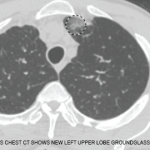

A third route may be to use dynamic, rather than static, criteria for classifying patients. In his work on scleroderma, for example, Colin Ligon demonstrated that serial measurements of forced vital capacity could be used to group patients into three categories, each of which was associated with a different probability of death.7 Working backward, it seems that calcinosis, among other factors, could be used to predict to which group a patient may ultimately belong. Presumably, a deeper meaning connecting calcinosis to lung function exists and is just waiting to be explored and exploited.