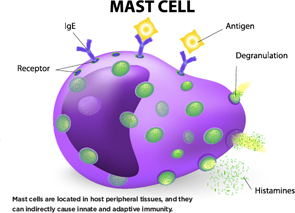

Mast cells are located in host peripheral tissues, and they can indirectly cause innate and adaptive immunity.

Designua/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—What factors help determine whether or not inflammation resolves, leading to healing, or becomes chronic, leading to disease and tissue destruction?

A number of important cells, including toll-like receptors, mast cells, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, complement and interferon, all play their own role in this process. By understanding how they act in innate and adaptive immunity and set off the disease process, rheumatologists may one day have more effective therapies to stop joint damage before it starts.

On Nov. 7, researchers at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting discussed the role some of these cells play in such diseases as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Toll-Like Receptors, Mast Cells & ACPAs

Mast cells are best known for their role in allergies, said Rene E. M. Toes, PhD, head of the Rheumatology Laboratory at Leiden University Medical Center in The Netherlands. After an antigen enters the bloodstream, there is mast cell degranulation and inflammatory mediators are released, he said. This can lead to life-threatening reactions in humans.

Mast cells are located in host peripheral tissues, and they can indirectly cause innate and adaptive immunity. They’re found in inflamed synovial tissue in both RA and osteoarthritis. In one study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology in 2015, the number of mast cells found in OA synovium went up along with higher Kellgren and Lawrence scores, measures of disease severity, he said.1

In RA, mast cells are mostly found in the joint sublining. In spondyloarthritis, they are in the synovial tissue.

“Mast cells express many pattern recognition receptors,” said Dr. Toes. “Toll-like receptors are among these. Are human mast cells activated through toll-like receptors? If so, which ones?” Mast cells respond to toll-like receptor ligands with the production of IL-8, he noted.

Both cultured and synovial mast cells express the receptor FCγRIIA.2 Mast cells are activated by immune complexes in an FCγRIIA-dependent fashion. Combined toll-like receptors and FCγR triggering induces synergy in cytokine production, Dr. Toes said.

Can mast cells be activated by anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) immune complexes? “ACPA recognizes many different citrullinated proteins. In RA, ACPAs are important markers of disease development,” he said. ACPA-positive RA patients have higher levels of immunoglobulin-G (IgG). Mast cells respond to ACPA, and endogenous toll-like receptor ligands enhance mast cell activation by ACPA.

‘Why do they have lupus? Because they can’t clear complement. … This points to the idea that if you can’t clear debris, there is a problem.’ —John P. Atkinson, MD

In addition, mast cells often co-localize with CD4 and T cells, and they can also process and present protein antigens. Mast cells specifically enhance Th17 responses. And in activated mast cells, IL-17 T cell response is enhanced, he said.

Upon activation, mast cells secrete active IL-1ß. That enhancement of Th17 responses by mast cells is mediated through IL-1ß. The release of IL-1ß by mast cells can influence T cell-independent responses. In RA, the synergy in cytokine and chemokine production may contribute to chronic inflammation.

Mast cells could be either anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory in arthritis, and the difference may depend on the timing of the infection of cells. Glycosylation may be important in mast cell activation with ACPA, Dr. Toes said.3

The Role of Complement

What do we know about the role complement plays in autoimmunity in diseases like lupus? Complement, part of innate immunity, acts to destroy and clear pathogens.Scientists first discovered the complement system during study of the lysis of bacteria. “E. Coli could be blown away by it quickly,” said John P. Atkinson, MD, director of the Division of Rheumatology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

In the humoral immune system, antibodies are specific, acquired and stable, while complement is innate, labile and non-specific. Antibodies and complement are both mediators of blood transfusion reactions.

In 1954, immunologist Louis Pillemer first described properdin, a complement factor, and an “alternate pathway of complement activation” that did not depend on antibodies, said Dr. Atkinson. Proponents of the classical pathway proponents attacked his ideas, but today, it’s accepted along with a third, the lectin pathway. All three pathways of complement activation generate variants of the protease C3.

Complement deficiency may make a patient more likely to develop infections like Neisseria meningitides or autoimmune diseases, such as SLE. Patients who are deficient in the complement component C1q have about a 90% chance of developing lupus, and those too low in C4 have a 75% chance, Dr. Atkinson said.4

“Why do they have lupus? Because they can’t clear complement,” said Dr. Atkinson. If immune complexes cannot be cleared, inflammation may be the end result. “This points to the idea that if you can’t clear debris, there is a problem.”

Patients who are deficient in the complement regulators Factor H and Factor I can’t control their complement system, and are vulnerable to infections, such as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, he said.5

Can we manipulate the complement pathway to help treat disease? Eculizumab is one complement inhibitor on the market. “It’s the most expensive drug in the world at $600,000 a year. It’s a monoclonal antibody that binds to C5 in the complement pathway, and it works,” said Dr. Atkinson.6 There is potential to develop therapeutic agents that block other complement factors and, in the future, possibly biosimilars, he said.

Factor H also plays a role in age-regulated macular degeneration, a chronic inflammatory disease. It’s caused by a defective regulation of the alternative complement pathway, which is continuously active in these patients. Certain variants in the Factor H gene increase risk for AMD, he said.7

Interferons in Lupus

What are the possible outcomes of a microbial infection? Resolution, peaceful coexistence or disease, said Mary K. Crow, MD, physician in chief, chair of the Department of Medicine, and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York.

An effective immune system rapidly destroys a microbe. But the microbe can persist in some hosts in a state of détente, in which the microbe and the immune system get along and coexist for a time. When can that situation go awry, leading to disease that could even be lethal?

“In autoimmune disease, maybe, the immune system starts to kill the host, destroying tissue and causing severe disease. So much depends on genetic variation,” said Dr. Crow.

Type-1 interferon is a central pathogenic mediator in SLE, she said.8 Genetic factors and pathways lead to a sustained expression of type-1 interferon in these patients. Type-1 interferon is a complex family of cytokines with diverse effects on the immune system. It binds to IFNAR, its receptor, and signals through the STAT-JAK pathway, she said.

Therapy with recombinant IFNα can induce lupus autoantibodies and clinical lupus. Lupus serum induces IFN production, and IFN gene expression signature is found in lupus blood, said Dr. Crow. A high IFN-type 1 test score is associated with increased disease activity. Interferon scores can fluctuate in the disease activity measures SLEDAI and BILAG.

In SLE, the type-1 interferon response just doesn’t shut down as it should, she said. In healthy people, there is rapid production of IFN-type 1, followed by diminishing viral load. In lupus, there is a sustained, prolonged and pathogenic immune response. Infection with the influenza virus leads to transient expression of IFN-induced genes in lung tissue.9 It’s a tightly regulated response to this viral infection, she said.

“Sustained production of type-1 interferon in a chronic virus infection is detrimental,” said Dr. Crow. “What happens here? The virus infection both drives and, in most cases, resolves the type-1 interferon response. What turns off the interferon response? It’s the virus. The virus inhibits induction of interferon. Proteins are made that inhibit the response to interferon.”

Viruses tend to actively mutate. For example, host-encoded and virus-encoded proteins have co-evolved in response to lentivirus infection, leading to long-term coexistence. But in lupus, it’s not caused by exogenous microbial infection. Host nucleic acid drivers of immune activation don’t encode inhibitors of viral restriction factors.

Drivers of interferon, such as endogenous cytoplasmic nucleic acids and nucleic acid-containing immune complexes, play an essential role in determining outcomes in SLE. There may be some potential for developing new lupus therapies by researching these drivers.10 Can we restore the host to that state of peaceful coexistence rather than active disease? Perhaps we can do so by mimicking the strategies that viruses use, Dr. Crow said.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.

References

- De Lange Brokaar B, Kloppenburg M, Andersen S, et al. Characterization of synovial mast cells in knee osteoarthritis: Association with clinical parameters. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Sept 29;67:(Suppl 10).

- Habets K, Trouw L, Levarht E, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies contribute to platelet activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015 Aug 24;17(1):209.

- Rombouts Y, Willemze A, van Beers J, et al. Extensive glycosylation of ACPA-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 25 Jan 2013.

- Park H and Atkinson J. Autoimmunity: Homeostasis of innate immunity gone awry. J Clin Immunol. 2012 Dec;32(60):1148–1152.

- Atkinson J and Goodship T. Complement Factor H and the hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Exp Med. 2007 Jun 11;204(6):1245–1248.

- Liszewski M and Atkinson JP. Complement regulator CD46: Genetic variants and disease associations. Hum Genomics. Epub ahead of print. 2015 Jun 10.

- Triebwasser M, Roberson E, Yu Y, et al. Rare variants in the functional domains of complement factor H are associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 Oct; 56(11):6873–6878.

- Crow MK, Olferiev M, and Kirou K. Targeting of type 1 interferon in systemic autoimmune diseases. Transl Res. 2015 Feb;165(2):296–305.

- Crowe S, Merrill J, Vista E, et al. Influenza vaccination responses in human systemic lupus erythematosus: Impact of clinical and demographic features. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Aug; 63(8):2396–2406.

- Crow MK. Advances in understanding the role of type I interferons in lupus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014 Sep; 26(5):467–474.