Renal osteodystrophy is associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and its associated metabolic derangements, most commonly CKD stages 3–5. It is often subclassified into four histological subtypes, with definite distinctions unable to be made clinically. These four subtypes, which may only be differentiated by bone biopsy, include: osteitis fibrosa cystica, mixed uremic osteodystrophy, osteomalacia and adynamic bone disease (see Subtypes of Osteodystrophy sidebar below).

Renal osteodystrophy occurs as a consequence of derangements in parathyroid hormone (PTH), phosphate and vitamin D that affect bone remodeling, leading to pathologically high or low bone turnover. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the leading cause of renal osteodystrophy.1

In the following case report, we discuss a patient with end-stage renal disease who presented to the hospital with significant hip pain that was originally attributed to a septic joint on the basis of imaging findings. We highlight the role of radiography in diagnosing renal osteodystrophy, highlighting the dangers of relying on imaging findings.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with end-stage renal disease, complicated by secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, who had been on hemodialysis for 14 years, presented with severe, intermittent, progressive left hip pain for two to three months leading up to admission. She denied any trauma to the area, fevers at home or other symptoms. Her pain was unrelieved by morphine, and she was unable to walk or move the hip given the severity of the pain. She denied morning stiffness or other joint pain, as well as a personal or family history of autoimmune disease. She had no known preceding viral illness.

On presentation, she was afebrile and non-tachycardic. Blood cultures were negative. A physical exam revealed full range of motion in both hips, but was notable for tenderness with internal and external rotation of the left hip. No other joint swelling was noted.

Her hemoglobin at baseline was 9.1 g/dL. Her white blood cell count was 5.7 B/L and remained within normal limits. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 30 mm/hour, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0.82 mg/dL. Parathyroid hormone intact was elevated at 2,305 pg/dL, calcium was 9.54.6 mg/dL, and phosphorous was elevated at 4.6 mg/dL. Alkaline phosphatase was elevated at 286 units/L.

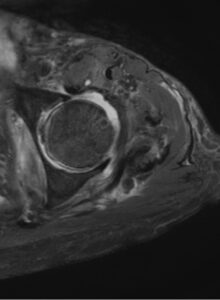

FIGURE 1: T2-weighted axial MRI of the hip with contrast showing periarticular erosion and left hip joint effusion. (Click to enlarge.)

An X-ray of her left hip revealed loss of the subchondral bone along the acetabulum concerning for a septic joint. She then had a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the hip that showed background changes of renal osteodystrophy involving the osseous structures of the bilateral sacroiliac joints and bilateral hip articulations, with findings concerning for superimposed left hip joint septic arthritis. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large joint effusion, periarticular erosion and synovitis, as well as edema involving the left periarticular musculature, most pronounced in the adductor compartment (see Figure 1).

Given the concern for septic arthritis, the patient underwent a joint aspiration that revealed only 255 white blood cells, 16% neutrophils, 13,760 red blood cells, and a negative gram stain and culture.

She was subsequently started on vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam while results were pending.

Given the non-inflammatory joint fluid, a diagnosis of erosive azotemic osteodystrophy, rather than osteoarthritis, was ultimately made. Antibiotics were stopped.

In discussion with radiology, findings of articular and periarticular erosions of the left hip consistent with erosive azotemic osteodystrophy had been present on a CT of her abdomen and pelvis performed nine months earlier. Her pain was managed with medications, she was seen by a physical therapist and, ultimately, discharged home.

Discussion

Our patient had studies conducted as part of an inpatient evaluation, with findings that mimicked a septic joint.

A study by Karchevsky et al. looked at the radiographic findings most commonly associated with septic joints. This study found that MRI synovial enhancement was present in 98% of septic joints, perisynovial edema in 84%, and joint effusions in 70%.2 The findings in our patient included joint effusions and synovitis, as well as periarticular muscle edema, therefore seemingly consistent with a septic joint. She was started on antibiotics, which were quickly stopped based on the sterile joint aspiration.

Ultimately, the patient’s hip pain was attributed to erosive azotemic osteodystrophy. The latest guidelines recommend against radiographic studies as a means of diagnosing erosive azotemic osteodystrophy due to the lack of consistent findings and correlation with clinical symptoms.

Bone biopsy is the gold standard for making the diagnosis of renal osteopathy and distinguishing its subtype, but is often deferred in clinical practice, with the diagnosis made by trending parathyroid hormone as well as markers of bone turnover, including alkaline phosphatase and C-telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX).3,4 However, radiographic findings associated with renal-related osteodystrophy include periarticular erosions, which may mimic inflammatory arthritis. Joint spaces, however, are generally preserved.4 Most common findings in the sacroiliac joints specifically include poorly defined erosions and articular sclerosis, often symmetrical. These findings were present on our patient’s radiographic studies.5

The incidence of articular erosions tends to increase with duration on dialysis. Thus, it is not surprising that our patient, who was on dialysis for 14 years, developed these lesions. Nevertheless, a study by Falbo et al. found only a 40% positive predictive value of radiographic erosions with regard to predicting clinically significant osteodystrophy, highlighting the lack of reliability of using imaging to assess joint pain with this condition.6

Our patient had secondary and tertiary hyperthyroidism. This is characterized by the inability of the kidney to convert vitamin D into its active form, as well as an inability to excrete phosphate, leading to overstimulation of parathyroid hormone. Moreover, the bone-derived hormone fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) is upregulated due to excessive phosphate retention, also leading to decreased production of active vitamin D. Given these derangements in the elements necessary for proper bone formation, nearly all patients with CKD stage 5 or higher develop some form of osteodystrophy.7

In Sum

Our case serves as an important reminder to consider erosive azotemic osteodystrophy on the differential for hip pain in a patient with long-standing kidney disease, despite radiographic findings that may point in a different direction. On the corollary, erosions are commonly found on imaging studies of CKD patients and do not always correlate clinically with symptoms, as discussed above. Therefore, it is important not to attribute joint pain to renal osteodystrophy simply based on radiographic erosions. Clinicians should further evaluate for an alternative diagnosis.

Ilana P. Goldberg, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia. She obtained her medical degree from Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston.

Ilana P. Goldberg, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia. She obtained her medical degree from Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston.

Samuel Faught, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia.

References

- Fukagawa M, Kazama JJ, Kurokawa K. Renal osteodystrophy and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17 Suppl 10:2–5.

- Karchevsky M, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, et al. MRI findings of septic arthritis and associated osteomyelitis in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004 Jan;182(1):119–122.

- Salam S, Gallagher O, Gossiel F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers and imaging for bone turnover in renal osteodystrophy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 May;29(5):1557–1565.

- Rubin LA, Fam AG, Rubenstein J, et al. Erosive azotemic osteoarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1984 Oct;27(10):1086–1094.

- Lobby MJ, Martel W. Some commonly unrecognized manifestations of metabolic arthropathies. Clin Imaging. 1992 Jan–Mar;16(1):1–14.

- Falbo SE, Sundaram M, Ballal S, et al. Clinical significance of erosive azotemic osteodystrophy: A prospective masked study. Skeletal Radiol. 1999 Feb;28(2):86–89.

- Fang Y, Ginsberg C, Sugatani T, et al. Early chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder stimulates vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2014;85(1):142–150.