Photo 1: The patient presented with heliotrope rash.

Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), a rare subset of dermatomyositis (DM), is an autoimmune disease characterized by cutaneous findings of typical DM without evidence of myositis. Childhood presentation of CADM is rare, and not many studies describe the epidemiology of juvenile CADM.1,2

Although lung disease is rare among patients with juvenile DM, a few reports have been published since 2007 about interstitial lung disease (ILD) in children with CADM.3 Rapidly progressive ILD occurs more in CADM patients than in classic DM patients and has a poor prognosis.

Several studies have been conducted to find the association between specific autoantibodies and ILD in patients with CADM. Autoantibodies to a 140 kDa cytoplasmic protein (i.e., anti-CADM-140 antibodies) were first described in adults with CADM in Japan.4,5 The antibody is directed against an RNA helicase encoded by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), which is a pattern recognition receptor that can induce the transcription of type I interferon genes in response to viral infection.6

Later, a strong association was seen between rapidly progressive ILD and the presence of anti-CADM-140 antibodies, also known as anti-MDA5 antibodies, in juvenile patients with both classic DM and CADM.7 Patients with juvenile DM who have anti-MDA5 antibodies can develop rapidly progressive ILD, which is associated with a worse prognosis. Prompt and aggressive intervention may improve outcomes, but can sometimes be challenging due to difficulty recognizing the disease, in part because of heterogeneous presentations, and failure to respond to conventional immunosuppression.

We describe a 6-year-old patient who presented with Gottron papules, heliotrope rash, mild muscle weakness and persistent fevers.

Case Description

The patient is a 6-year-old Black child who presented with symptoms of mild muscle weakness and persistent fever up to 103ºF. The febrile episodes occurred almost every other day for about four to five months. He later developed joint pain, mainly involving his knees and elbows, with erythema and swelling. His mother noted a rash around her son’s eyes and on his hands about a month prior to presentation.

The patient was seen by his primary care physician and laboratory tests were obtained (see Table 1). The patient was referred to our hospital for further evaluation.

On examination, the patient was noted to have a heliotrope rash (see Photo 1) and Gottron papules (see Photo 2), Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers on the distal tips of his thumb, index and middle finger (see Photo 3); and mild weakness of his arms and legs.

Magnetic resonance imaging of both legs showed a mild increase in signal intensity in the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius and hamstring muscles in both legs. Treatment was initiated with 30 mg/kg/day intravenous steroids for three days and 10 mg of subcutaneous methotrexate once a week. He experienced an initial improvement of his weakness and rash. However, during the intervening four weeks before his follow-up appointment, the weakness and rash worsened. Steroid administrations were repeated, and 1 gm/kg intravenous immunoglobulin was administered once daily for two days.

Photo 2: Gottron papules were evident on the patient’s hands at presentation.

Photo 3: The patient had a purplish discoloration and digital ulcers on the distal tips of his thumb, index and middle fingers.

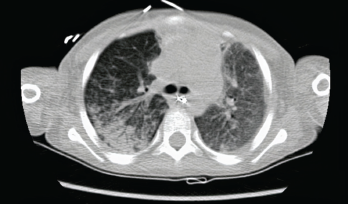

Photo 4: The initial chest CT showed diffuse bilateral airspace opacities.

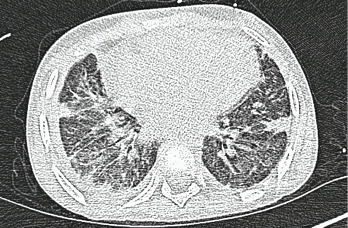

Photo 5: A high-resolution CT scan after one month shows interstitial thickening opacities and thickening of the interlobular septa.

About three weeks later, the patient presented with respiratory distress. He had been short of breath for three days, and his condition had worsened to the point that he could not complete sentences. He was taken to an emergency department for evaluation, where he was noted to be tachypneic, tachycardic and hypoxic (pulse oximeter: with ≈70% on room air), with a fever of 101ºF. The patient was placed on a non-rebreather face mask and airlifted to our pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Table 1: Initial Labs on Presentation

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 882 units/L (15–37) |

|---|---|

| Alanine aminotransferase | 208 units/L (12–78) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 180 units/L (45–117) |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | <0.29 mg/dL (0.0–0.3) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 13 mm/hr (0–15) |

| Creatine kinase | 163 units/L (26–308) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 858 units/L (87–241) |

| Ferritin | 1,929 ng/mL (8–388) |

| Aldolase | 30.3 units/L (2.2–7.8) |

| Anti-nuclear antibodies | Negative |

Table 2: Labs Obtained After Patient Transferred to Our PICU

| White blood cells | 22.56 k/uL (5–14.5) |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 9.2 g/dL (11.5–15.5) |

| ESR | 93 mm/hour (0–15) |

| CRP | 18 mg/dL (0–0.3) |

| Procalcitonin | 104 ng/mL (>1.9—high risk of sepsis) |

Upon arrival to our PICU, the patient’s tachypnea was slightly improved. The patient’s oxygen saturation was 92% while using the non-rebreather face mask. On examination, he was in respiratory distress with suprasternal and subcostal retractions, and auscultation revealed coarse breath sounds. The physical examination was notable for a swollen right wrist and right knee, concerning for septic arthritis. Gottron papules and a heliotrope rash were noted, along with digital ulcers (see Table 2). A chest X-ray showed bilateral airspace opacities concerning for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The PICU team initially thought the patient had developed ARDS secondary to septic arthritis. Thus, he was emergently taken to an operating room and intubated prior to an arthroscopic knee washout to achieve source control. He was unable to be extubated following the procedure.

Synovial fluid cultures grew methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment was initiated with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam, initially, and then switched to nafcillin to narrow the spectrum of antimicrobial coverage.

The patient’s respiratory status continued to decline. He had difficulty maintaining oxygenation despite mechanical ventilation. A computed tomography (CT) chest scan was obtained, which showed diffuse bilateral airspace opacities (see Photo 4).

The patient’s respiratory status worsened despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy. We suspected the patient’s respiratory decline was due to underlying rapidly progressive ILD associated with CADM, rather than sepsis. We recommended immediately placing the patient on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and initiating plasmapheresis. We later added high-dose steroids (30 mg/kg daily for three days, followed by 1 mg/kg every six hours). Serum anti-MDA5 antibody levels were ordered at the same time.

The patient’s respiratory status significantly improved following plasmapheresis. He was extubated three days after initiation of ECMO and was weaned off ECMO after five sessions of plasmapheresis.

The patient was found to have anti-MDA5 antibodies, and the patient was administered 575 mg/m2 of intravenous rituximab (pediatric myositis dose for a patient with a BSA of <1.5), with a second dose one week later.

Prompt & aggressive intervention improves outcome, but can sometimes be challenging due to the rarity of CADM, heterogeneity of disease manifestations & refractoriness to conventional immunosuppression.

The patient demonstrated gradual clinical improvement and was eventually discharged on 2 L/minute of oxygen after a prolonged and complicated hospital stay of six weeks. Repeat anti-MDA5 antibody titers showed a decline of 80 units after a month.8,9 MDA-5 antibody titers may correlate with treatment response, although this is has not been observed by all groups. A high-resolution CT scan obtained a month after hospital discharge showed thickening of the interlobular septa, numerous cystic-appearing lesions and interstitial thickening opacities, which were consistent with stable ILD (see Photo 5).

Discussion

Juvenile DM is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by proximal muscle weakness and a pathognomic rash. Anti-MDA5 antibodies were originally described in a subset of patients with amyopathic DM.

The role of MDA5 and anti-MDA5 antibodies in the pathogenesis of DM is not clearly understood. It is thought that antibody production occurs during viral infection of the skin and lung epithelium, and is triggered by the release of MDA5 from infected cells. Antibodies are believed to injure endothelial cells and other tissues. The incidence of myositis-specific antibodies in juvenile DM is 10%. The prevalence of anti-MDA5 antibodies is 6%. The anti-MDA5 antibody is associated with clinically amyopathic or hypomyopathic DM, ischemic cutaneous ulcerations, rapidly progressive ILD and a poor prognosis.

Although our patient presented with weakness, his creatinine kinase was normal and the MRI revealed minimal muscle edema; given this and the presence of ILD, we believe his presentation was more consistent with juvenile CADM than with juvenile DM.

Rheumatologists should be aware of anti-MDA5 antibody-associated rapidly progressive ILD in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis, the aggressive nature of the disease and the need for equally aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

Anusha Vuppala, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at LSUHSC.

Anusha Vuppala, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at LSUHSC.

Sarwat Umer, MD, is an associate professor of rheumatology at the Center of Excellence for Arthritis and Rheumatology in Shreveport, La. Dr. Umer completed her adult rheumatology fellowship at Louisiana State University Health Science Center (LSUHSC), Shreveport, and pediatric training at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Sarwat Umer, MD, is an associate professor of rheumatology at the Center of Excellence for Arthritis and Rheumatology in Shreveport, La. Dr. Umer completed her adult rheumatology fellowship at Louisiana State University Health Science Center (LSUHSC), Shreveport, and pediatric training at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Samina Hayat, MD, for her mentoring advice and continued support for pediatric rheumatology. Dr. Hayat is chief and director of the Center of Excellence for Arthritis and Rheumatology at Shreveport, La.

References

- Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 30;372(18):1734–1747.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1975 Feb 13;292(7):344–347.

- Gerami P, Walling HW, Lewis J, et al. A systematic review of juvenile-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Oct;157(4):637–644.

- Sato S, Hoshino K, Satoh T, et al. RNA helicase encoded by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is a major autoantigen in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: Association with rapidly progressive interstitial disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jul;60(7):2193–2200.

- Hamaguchi Y, Kuwana M, Hoshino K, et al. Clinical correlations with dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies in adult Japanese patients with dermatomyositis: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2011 Apr;147(4):391–398.

- Tansley SL, Betteridge ZE, Gunawardena H, et al. Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies in juvenile dermatomyositis identify a distinct clinical phenotype: A prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Jul 2;16(4):R138.

- Pachman LM, Khojah AM. Advances in juvenile dermatomyositis: myositis specific antibodies aid in understanding disease heterogeneity. J Pediatr. 2018 Apr;195:16–27.

- Yashiro M, Asano T, Sato S, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive hypomyopathic dermatomy ositis complicated with pneumomediastinum. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2018;64(2):89–94.

- Endo Y, Koga T, Ishida M, et al. Recurrence of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis after long-term remission: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jun;97(26):e11024.