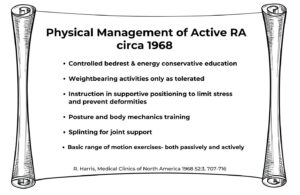

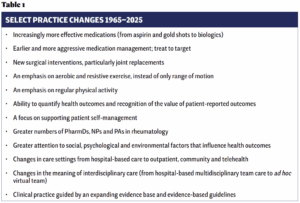

Over the past 60 years, new medications, such as biologics, and new surgical procedures, such as total joint replacements, have dramatically improved patient health outcomes and quality of life. At the same time, non-pharmacological treatments have undergone profound change as well. In 1968, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis emphasized bed rest, range of motion exercise and didactic patient education (see Figure 1).1 This contrasts dramatically with today’s emphasis on aerobic, resistive and balance exercise, and self-management education and support.2

Additionally, the location and model of interdisciplinary care has shifted from predominantly hospital-based team care in the 1970s to today’s decentralized, virtual teams tailored to discrete patient needs. We presented a precursor to this article at ACR Convergence 2024 and encouraged audience members to reflect on changes in practice they had observed (see Table 1). The audience reminded us of what we no longer see: specifically, patients whose mobility depends on a wheelchair. Likewise, it is rare to encounter patients with severe contractures, patients who are severely deconditioned or patients with limited information on how to care for themselves. Our evolving practice has significantly enhanced patient outcomes. Through continued collaboration, we can build on this progress.

These changes have also led to some unintended consequences. The shift toward earlier and more aggressive medication management, with its impressive reductions of inflammatory markers, may overshadow the fact that the physical and mental health statuses of patients are not improving in tandem with reductions in inflammation.3 For example, not all patient pain is inflammatory in nature, and life disruption secondary to the disease or condition often persists. This highlights the importance of interdisciplinary care; ARP members are experts in addressing these patient needs.

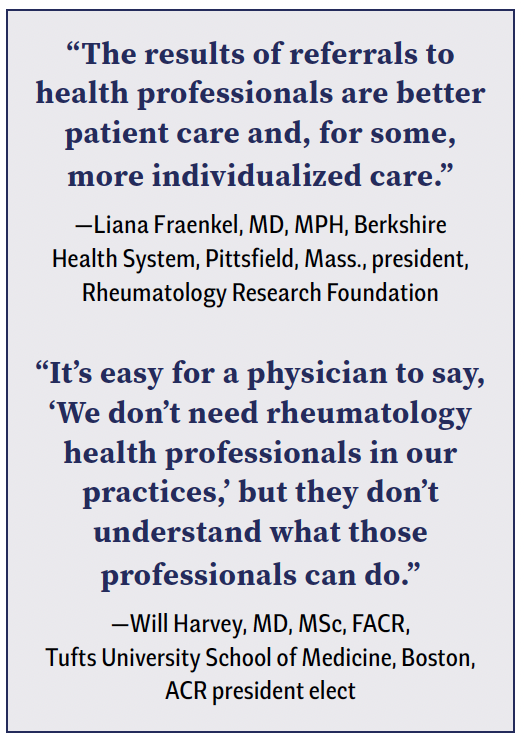

Further, the move to decentralized outpatient and community-based care has complicated interdisciplinary collaboration and communication. In this model, rheumatologists and advanced practice providers (APPs), such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), are located in one setting, and clinics of physical therapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs), social workers, psychologists, pharmacologists, orthotists and other health professionals operate in separate locations. In some instances, this decentralization has reduced referrals to these services and disrupted the cohesive understanding of how each discipline contributes to enhancing patient quality of life.

To ensure patients receive the most comprehensive and effective treatment and achieve optimal quality of life, clinicians must be vigilant in identifying issues and concerns that may be better managed by other disciplines. Clinicians must have expansive referral networks and expedited interdisciplinary communication protocols.